Local Women: Re-Writing Gender Stereotypes

Over the years there have been many exceptional and heroic women in the Lancaster and Morecambe district who have excelled or led in such diverse areas as acting, flying, nursing, botany, teaching, art, football, gathering mussels and cryptology, as well as running inns, lighthouses, a Friendly Society, and the Post Office.

All this before we even start to talk about the women who have been involved in politics, when it was very much male-orientated, and the Suffragette Movement in establishing the right for women to be able to vote.

Lynne Braithwaite - RAF Officer & Transgender Activist

Lynne Braithwaite was born Lawrence Braithwaite in the Lake District in 1934. After serving 40 years in the RAF, she retired as a flight sergeant in 1989 and shortly thereafter transitioned to female. From that point until her death in 2008, Lynne was actively involved in training and awareness-raising about transgender issues within the Lancashire Constabulary and other local services, a process she instigated when she saw there was a vital need for it.

“Wherever Lynne went, her training “always went down an absolute storm… She would make them laugh and that’s one of the best things you can do in a training session, especially about an awkward subject for some people.”

For more information about Lynne visit – Lynne Braithwaite

Evaline Hilda Burkitt - First Suffragette to be Forcibly Fed

Hilda joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1907, coordinating the Birmingham group’s publicity and fundraising. She was arrested 4 times in 1909, the last time for throwing a stone at the train carrying Prime Minister Herbert Asquith to a political meeting in Birmingham. In prison, the suffragettes were treated as common rather than political criminals. In protest at this, and to draw further attention to their cause, they went on hunger strike. Fearful that the women might die during their imprisonment, the authorities went to great extremes to force feed them. Hilda Burkitt was the first suffragette to undergo force feeding.

For more information about Hilda visit – Evaline Hilda Burkitt

Sister Aine Cox MBE - First Matron of St John's Hospice, Lancaster

.jpg)

Sister Aine had the gift of making everyone feel special with a feeling of belonging and peace, whether it was someone in need of care, the homeless or even a stray dog. She was welcoming towards all. In 1987 Sister Aine received the MBE for services to the Hospice movement and in 1989 she received an Honorary Degree LLD from Lancaster University. In 1994 Lancaster City Council awarded her the Honorary Freedom of the City.

For more about Sister Aine and St John’s Hospice visit – Sister Aine Cox

Muriel Dowbiggin - Suffragist & Peace Activist

Politician, suffrage campaigner, mayor and peace campaigner. Muriel was a member of the Women’s Liberal Association and the Women Citizens Association. She was an organiser for the League of Nations Union, the international peace organisation formed at the end of WWI. In the 1920s she was elected as a city councillor, becoming Mayor of Lancaster in 1940 (the third woman to hold this position). She was also a Governor for Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School.

For more information about Muriel visit – Muriel Dowbiggin

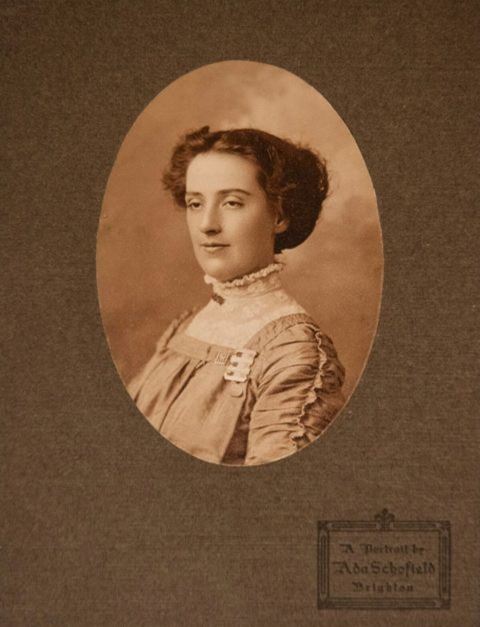

Elizabeth Glasson - Postmistress

This framed portrait from our collection is entitled Mrs Glasson, Widow of a naval officer, and Postmistress of Lancaster (circa 1843-1853). A bit of research tells us that this caption is only partly accurate, but Mrs Glasson’s story gives us an intriguing snapshot of life in 19th-century Lancaster.

Elizabeth Moffat Glasson (nee Weir) was born on 26 August 1789 in St. Ann, Jamaica. Her mother was Elizabeth Collett Johnston (nee Gilbert), and her father was Dr Alexander Weir, a plantation doctor for St.Annes.

Dr Weir was Elizabeth’s mother’s second husband, following the death of her first husband and Weir’s business partner, the very ambitious plantation doctor Dr Alexander Johnston. Despite Johnston’s estate being valued at around £19,300 at the time of his death in 1787 (equivalent to about £3.8 million today!), Elizabeth’s mother was left nothing in his will except the original 300 acres that came with her as her dowry. Dr Johnston’s two ‘illegitimate’ children (had by a slave in a neighbouring town) had their freedom bought and were left a slave each. His four ‘legitimate’ sons shared the valuable estate between them. Their sister received £100. Elizabeth Johnston went on to marry Dr Weir soon after Dr Johnston’s death and they had two girls, Elizabeth and Isabella. Weir died in 1794, once again leaving Elizabeth’s mother a widow.

Elizabeth’s story goes quiet for a while but at some point in the next 19 years she crosses the Atlantic: according to the Registry of Marriages at St. Mary’s Church (Lancaster Priory), Elizabeth Moffat Weir married John Cornish Glasson in Lancaster on 12 June 1813. John was a soldier in the 2nd Queen’s Royal Regiment, based in Sussex. They went on to have three children, though their son James died before his first birthday. Elizabeth’s husband died in 1820 in Demerara, Guiana, at the age of 35, leaving her a widow after only seven years of marriage. Elizabeth would continue to receive John’s pension of £40 a year from the army. At no point was he ever registered as a Naval Officer. Perhaps this is a story that Elizabeth used to tell to uplift her status.

Again, we lose sight of Elizabeth for a while. She may have been able to live on her savings, pension and inheritance for some time before deciding to seek paid employment. But here her options would have been severely limited. Middle-class women were expected to remain at home, and if circumstances forced them to make their own living then opportunities for ‘respectable’ employment were few and far between. In the previous century, becoming a governess or teacher had been almost the only socially acceptable alternative to marriage. In the Victorian era, nursing and secretarial work were added to the list. The Post Office also employed an increasing number of women. Some inherited their positions from their parents or husbands, but many others, like Mrs Glasson, were appointed on their own merits. She first pops up on the Post Office payroll when she was appointed as a Deputy Postmaster in Lancaster in 1833, working under Miss Elizabeth Noon, who had managed the Lancaster Post Office since 1825. Elizabeth was required to be covered by a penalty bond of £1000 to the Post Office upon her appointment. (That’s around £68,000 today!) This was the rate set for Lancaster at the time and covered her in case she failed to perform her role satisfactorily. They needn’t have worried, Elizabeth served for ten years as Deputy and another ten years as Postmaster, until 1853 when she retired aged 64. The official age of retirement in the Post Office at this time was 60 years old.

In 1836 an E.M. Weir made a successful compensation claim for two enslaved people whom she claimed to own in Jamaica. This was possibly Elizabeth, as many people living in England still owned slaves or shares in enslaved people or plantations in the West Indies and Americas up until the passing of the Abolition of Slavery Act in 1833. They may well still have been registered in her maiden name.

In 1851 Elizabeth is shown on the Lancaster Census as living on Market Street, Lancaster. She lives with her daughter Eliza, who is Assistant Postmaster and a spinster aged 30. They have two members of staff: Mary Brewer, a 15-year-old Housemaid, and Elizabeth Baines, who is 18 and their Cook. By 1861 Elizabeth is recorded as living with her son George Johnson Glasson in Poulton, Bare. George’s occupation is recorded as a Coffee Planter. She died on 28 Jan 1881 in Kensington, London. She was 92 and had lived as a widow for 61 years.

Elizabeth’s story, her connection to plantations in Jamaica and the transatlantic slave trade through her parents and her possible claim for two enslaved people following the abolition of slavery show how deep-rooted the trade was among seemingly ordinary people.

To find out more about Lancaster's involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, visit Lancaster Maritime Museum, join one of our walking tours or read this article on our website: Transatlantic Slave Trade

It is only with help from the Postal Museum in London, census records, military pension records, parish registers, and private family records that we have been able to build this picture of Elizabeth’s life.

Selina Martin - Suffragette

On 21 December 1909 Selina Martin and Leslie Hall approached the Prime Minister as he was leaving his car, and tackled him on the subject of women’s rights. He didn’t answer them, causing Selina Martin to throw an empty ginger beer bottle into the empty car. She was arrested and imprisoned, being force fed and treated as a criminal even before her trial.

For more information about Selina visit: Selina Martin

Image courtesy of the People’s History Museum.

Noreen Murray - Molecular Geneticist

Noreen Parker moved to Bolton-le-Sands in 1940, aged 5. She attended Lancaster Girls’ Grammar School before studying botany at King’s College London and the University of Birmingham, where she received her PhD. She worked at Standford University, Cambridge and the Medical Research Council before settling at the University of Edinburgh. Working with her biochemist husband, Kenneth Murray, she helped develop a vaccine against Hepatitis B. This was the world’s first genetically engineered vaccine to receive approval for human use, and her work helped pioneer genetic engineering.

For more information about Noreen visit – Noreen Murray

Patricia & Jean Owtram - WW2 Codebreakers

.jpg)

Both sisters worked decoding messages during the Second World War. Patricia joined the WRNS at Y stations in Yorkshire and the South coast, listening for enemy messages and translating and decoding them. Jean joined FANY, but worked as a cipher, supporting the Special Operations Executive in Egypt and Italy, decoding messages from spies and informants and sending coded messages. After the war Patricia became a journalist, working for the BBC and Jean was instrumental in setting up Lancaster University.Patricia received the Legion d’honneur in June 2019. You can watch an intimate conversation with her following the ceremony entitled Tea For Two.

For more information about Patricia & Jean:

- Read this article - Owtram Sisters

- Watch this video - Patricia Owtram's Story

- Or read the widely available book pictured here: Codebreaking Sisters, Our Secret War.

Mabel Pakenham-Walsh - Artist & Disability Campaigner

Mabel Pakenham-Walsh studied at Lancaster and Morecambe College of Arts and Crafts, 1957. Born with congenital hip dysplasia, she suffered lifelong physical disability. Consequently, Pakenham-Walsh campaigned throughout her life for disability rights, especially for children and youths, and for better access to public buildings for people with disabilities. She was employed as a designer at Pinewood Studios, where she created set-pieces for major motion-pictures, including Cleopatra; she also worked as a sculptor at Shepperton Studios. Many of her works were made in a naive style, using found or recycled materials. This was initially a necessity borne out of a lack of financial support for female artists. In the 1970s she moved to Aberystwyth, where she created a series of carvings depicting local legends.

For more information about Mabel read her obituary: Mabel Pakenham-Walsh

Mary Agnes Wilkinson - WW1 Telephonist

.jpg)

Mary was a telephonist at the Cable Street exchange. On the night that the White Lund shell filling factory exploded, October 1st and 2nd 1917, Mary was called from her home on the Marsh to come on duty. She cycled through the danger zone with explosions on the opposite side of the river knocking her from her bike twice and made it to the exchange, staying on duty for over 24 hours to make sure messages could get through. For her bravery and dedication that night, Mary Wilkinson was awarded the British Empire Medal.

For more information about the explosions at White Lund in 1917, read this article from the Heaton-with-Oxcliffe Parish Council

Or visit the local history galleries at Lancaster City Museum.

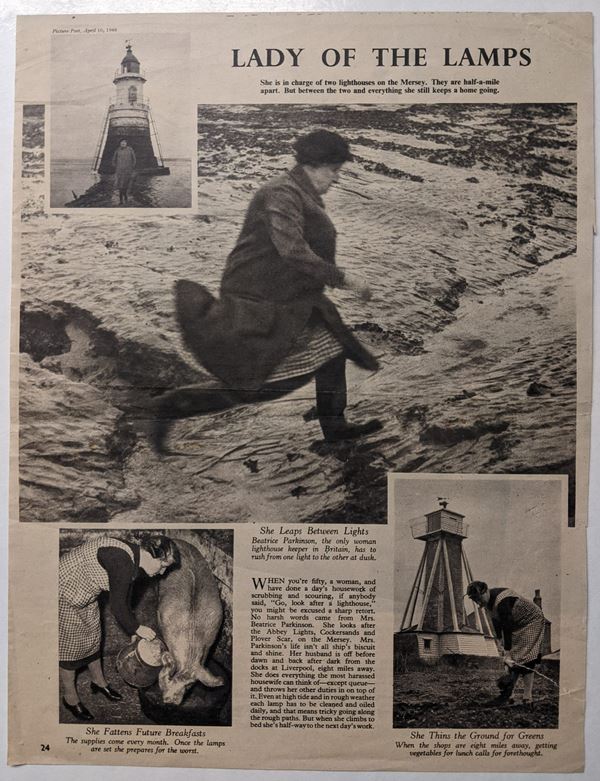

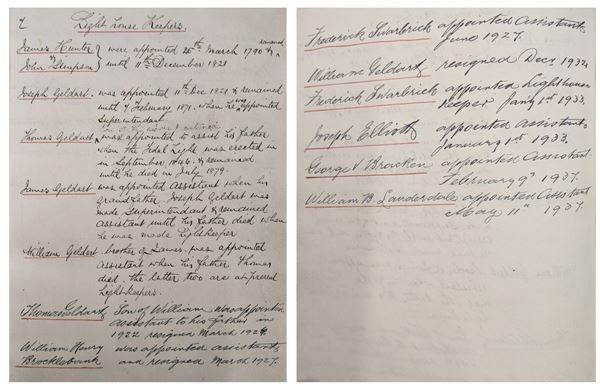

The Lighthouse Keepers

‘Of all the unusual occupations of today, lighthouse keeping is one field you might legitimately expect to be reserved for men only.’

So says the Pathe News reader at the start of this short film from 1948.

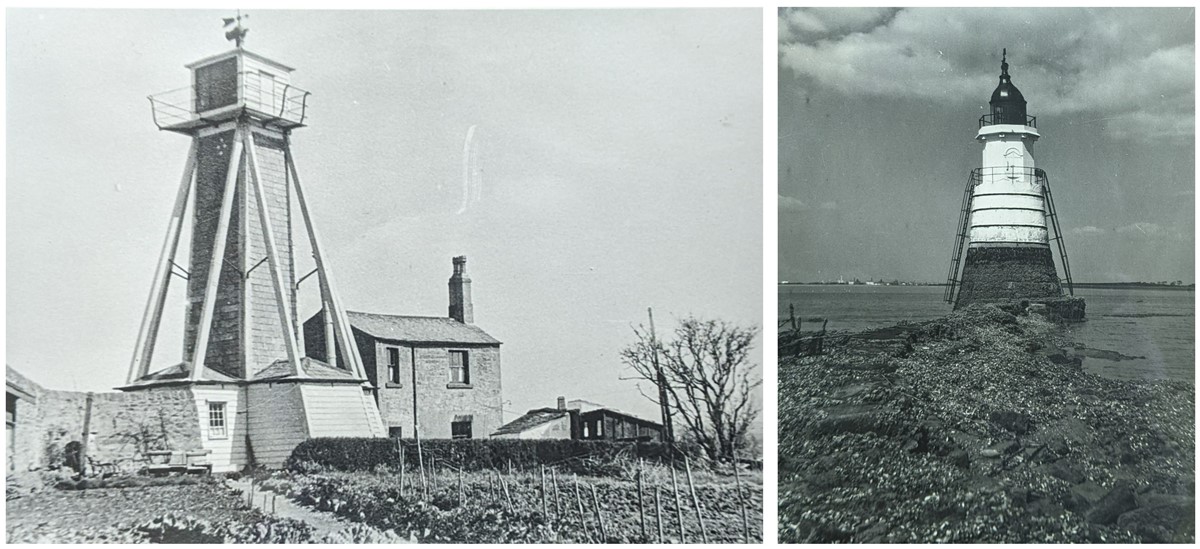

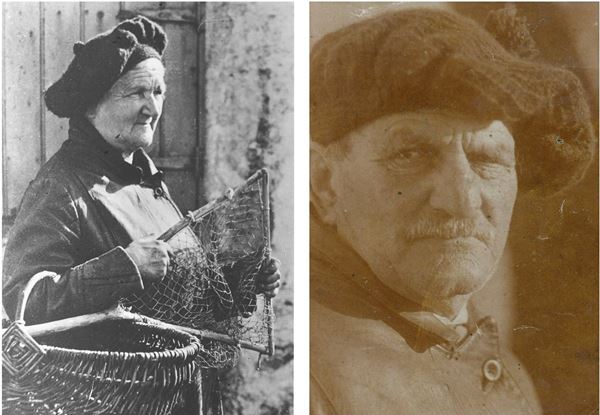

‘But it isn’t’, he continues, and goes on to show us the work of Beatrice Parkinson, ‘a lighthouse keeper in her own right’ for the twin lights of Cockersands Abbey and Plover Scar at the Mouth of the River Lune.

With this appearance in film, and with articles in the national press, Beatrice Parkinson briefly shot to fame as ‘the only woman lighthouse keeper in Britain’. Hers was an inspiring story about perseverance in the face of unique hardships. Just what was needed amid the grim realities of post-war Britain. But was she really so unusual?

When the Parkinson family moved into the keeper’s cottage at Cockersands in 1945, it was Beatrice’s husband Thomas who’d been appointed as Keeper. But a recent oral history project gave their son Bob the chance to explain how his mother soon took over much of the work on the lights, allowing Thomas more time for his other occupation as a fisherman:

‘Me father used to sell all t’fish and he’d to knock off to do t’light’ouse so me mother said, “If I can do it – I‘ll go and see if I can get up that light,” and that’s when it started yer see, “If I can get up there,” she says, “I’ll do it for you so as you [can carry on.]”’

Bob goes on to add that from the age of eleven he too had been helping with the lighthouses, cleaning and refilling the lamps with paraffin before starting school and after he came home. In the middle of the day it was his mother’s job. In short, he makes it clear that far from being ‘reserved for men only’, lighthouse keeping was a family affair.

The Parkinson family was far from alone in this arrangement. It’s true that lists of lighthouse keepers everywhere are filled with male names, the job often passing from father to son through many generations of a single family. But there’s no doubt that in reality, most of these men would have shared the work not only with their sons but also with their wives, daughters and sisters. The work of these women went largely unrecorded and unrewarded, taken for granted as part and parcel of the official positions of their menfolk. Only occasionally did it come to light, as with Beatrice Parkinson or in the better-known case of Grace Darling – a lighthouse keeper’s daughter who became famous in 1838 for her part in the rescue of survivors from a shipwreck. The public interest in her life revealed that along with her mother and sisters, Grace was quite used to taking an active part in maintaining the lighthouse that was nominally kept by her father.

Most lighthouses in England and Wales are under the authority of Trinity House. By the end of the 1990s all of their lighthouses were automated, but until then then they were responsible for hiring full-time keepers. Over four centuries or so, the organisation never once appointed a woman as Principal Keeper of a lighthouse, although the contributions of the keepers’ wives were sometimes acknowledged with the title of Female Assistant Keeper.

Some areas of the country have their own Local Light Authorities, which seem to have been more flexible than Trinity House. In Chester, Mrs Cormes was appointed as keeper of the Point of Ayr lighthouse as early as 1791. Liverpool has had a number of female lighthouse keepers from 1797 onwards. Here in Morecambe Bay, the Local Light Authority is the Lancaster Port Commission. They own and maintain all the aids to navigation on the River Lune, including the lighthouses at the mouth of the river and on Walney Island. And while Beatrice Parkinson may not have been officially taken on as a lighthouse keeper by the Commission, several other women were:

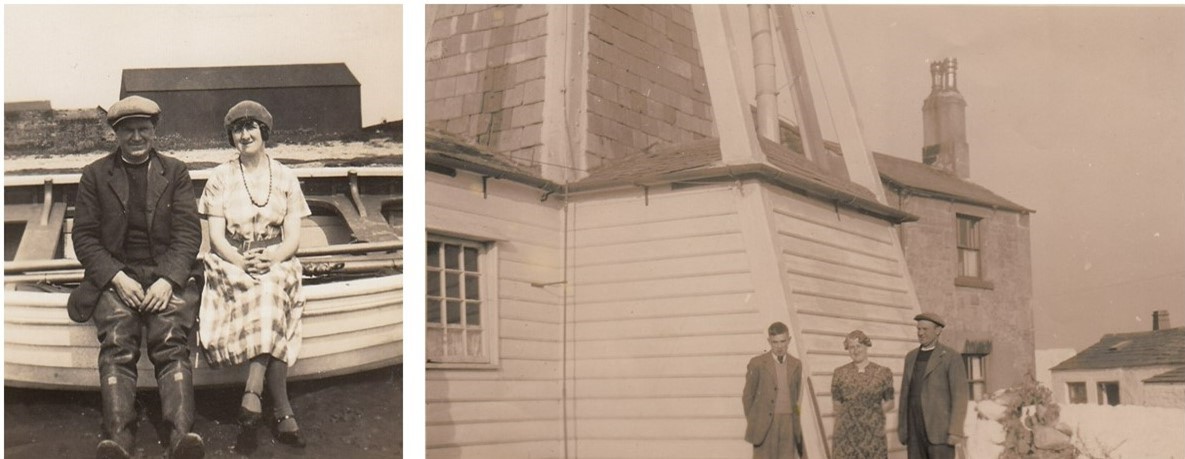

Before the Parkinsons took over in 1945, the pair of lights at the mouth of the Lune had been kept by Janet Raby, who was employed by the Lancaster Port Commission at a rate of £8 per month. She was assisted by her brother, Dick, who lived in a separate cottage in Thurnham. They often shared the work by looking after one light each. Both of them also divided their time between working the lighthouses and fishing the Bay. They were the third and last generation of the Raby family to maintain the Lune lights – their grandfather Francis had been the first keeper, appointed in 1847 when the two lighthouses were constructed.

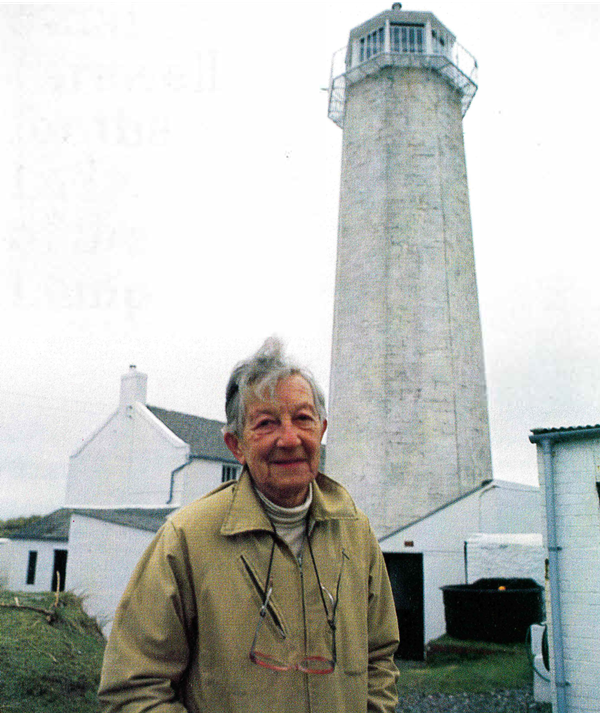

On the other side of the Bay, Fred Swarbrick became Assistant Keeper of Walney Lighthouse in the 1920s, and Principal Keeper in 1933. He had two daughters, Ella and Margaret (Peg), who both grew up around the lighthouse. By the 1940s Ella was employed by the Lancaster Port Commission as Assistant Keeper, working alongside first her father and then her husband Albert. Meanwhile, Peg was paid a retainer to act as relief keeper during holidays or sickness, sometimes managing the lighthouse single-handed for weeks at a time. Besides the technical work of keeping the lights, Peg and Ella were responsible for maintaining the keepers’ cottages, the lighthouse tower and the surrounding area. The exposed position of the buildings made this a herculean task; between the 1940s and 1960s they had to repaint the outer walls of the entire lighthouse tower every other year.

Peg, now known by her married name of Braithwaite, took on the full-time job of Assistant Keeper after Ella’s death in 1967, and then became Principal Keeper in 1974 when Albert retired. A decade later she was awarded the British Empire Medal for her long and exceptional service. The Chairman of Lancaster Port Commission wrote her a glowing recommendation, including the fact that she ‘never expected or considered that she should have special treatment on account of being a woman. On the contrary, she felt herself to be a lighthouse keeper quite simply, and carried out her duties accordingly; although at times her courage was tested to the limit and never found wanting – one night she pushed the light round all night by hand when the mechanism failed.’

This interview from a few years before Peg’s retirement in 1994 attempts to draw out more tales of the extraordinary challenges of lighthouse keeping, but Peg is pragmatic about her work. Like generations of women before her, she takes it all in her stride, and that ‘legitimate’ expectation of the 1940s is shown once and for all to be anything but legitimate.

Lancaster Port Commission has been of great help in providing access to their historical records for this article. Their website has more information on their history and current activities: lancasterport.org

Recording Morecambe Bay has a huge collection of photos, oral history and and information on local lighthouses and their keepers: recordingmorecambebay.org.uk

Bidston Lighthouse has a blog post looking into the history of female lighthouse keepers in Britain: bidstonlighthouse.org.uk

Cumbria and Lakeland Walker magazine has an article about Peg Braithwaite, written on her retirement in 1994: cumbriamagazine.co.uk