Place-Names of the Lancaster District

Every place-name has a meaning, usually one that dates back more than 1,000 years.

The Lancaster district roughly covers the ‘South of the Sands’ section of the old Hundred of Lonsdale.

It is an area for which written records simply do not exist before the Domesday Book of 1086.

What we know of the history of the Lancaster district therefore has to be pieced together. We use archaeology, metal detected finds, place-names, surviving stone sculpture and rare survivals such as St Patrick’s chapel at Heysham.

2022 was the centenary of the publication of ‘The place-names of Lancashire’ by Eilert Ekwall. To celebrate we ran a series of facebook posts looking at local place-names and featuring photographs from the museum collections. These posts have now been transferred to this website and we will continue to add to the list over time.

Choose a place-name from the list below to learn about its origins.

Aldcliffe

Aldcliffe was first recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Aldeclif’. A place-name starting with ‘Ald’ can often mean ‘Old’ – for example Aldborough in North Yorkshire is the ‘Old Borough’ (fortification) – in this case a Roman tribal capital or ‘civitates’.

However, this is not the case here, as Aldcliffe is a straightforward Anglo-Saxon place-name meaning Alda’s cliff or slope. Alda was a fairly well-known Anglo-Saxon name and the land slopes up to around 100 feet close to where Aldcliffe Hall was sited.

Although we think of cliffs as being steep, originally they could also be a slope – although one that might be quite noticeable locally. Many are close to water and Aldcliffe is near the Lune. The medieval Aldcliffe Hall would have had good views across the river.

Historically Aldcliffe was linked to Bulk. Along with Lancaster Priory, the two were granted to the Abbey of St Martin’s at Sées in Normandy in 1094. From then on they seem to have been paired together as though they were one estate.

In 1557-8 following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the two estates were sold to the Catholic Dalton family of Thurnham. Along with Dolphinlee, Aldcliffe Hall became a centre for Roman Catholicism, which was practised illegally during the late 1500s and 1600s.

The photo shows the old cottages at Aldcliffe with the land sloping upwards behind them.

Arkholme

Arkholme has an extremely interesting place-name. Unlike many of the other place-names that we have looked at, Arkholme looked very different in the Domesday Book when it was referred to as ‘Ergune’. It only became ‘Erholme’ in the 1500s.

The first part of Arkholme comes from ‘erg’ and place-name scholars are still debating exactly what this means. It is connected to animal farming, signifying a small settlement where cattle were pastured during the summer.

It now seems to be likely to be connected to the medieval vaccary system in northern England. These were large-scale cattle management enterprises which produced oxen for ploughing and cattle for meat, hides, milk and cheese. There is a suggestion that this form of cattle rearing was perhaps pre-Roman. The word itself seems to have originated in Celtic Ireland and western Scotland as ‘áirge’ and was probably brought over by Scandinavian settlers in the 900s.

Unusually, and unlike Dolphinholme and Torrisholme, the ’holme’ part developed from the original ending -um, meaning ‘at the ergs’, and doesn’t relate to being by water – even though it is! Arkholme was of strategic importance and had a Norman defensive motte. This one was half of a pair with the motte at Melling, directly across the Lune.

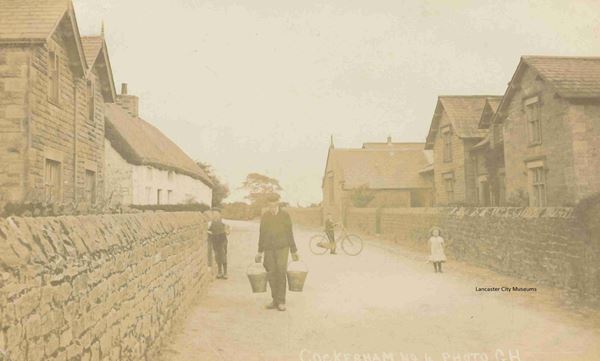

The photo shows Main Street, Arkholme around 1900-1920 looking towards the crossroads with the Carnforth to Kirkby Lonsdale Road.

Arnside

Arnside is an Ango-Saxon placename that was first recorded around 1184-90 as ‘Harnolvesheuet’ or ‘Arnulf’s headland’ from the Anglo-Saxon name Earnwulf and the Old English hēafod.

It was only around 1517-19 that is started being referred to as Arn(e)sid(e) or Arn(e)syde. The ‘knott’ comes from an Old Norse word knǫttr, meaning ' rocky hillock '.

In the 1700s it was referred to as ‘the Kinges parke and chase of Harneshed’, seeming to indicate that it was once at least a royal hunting ground.

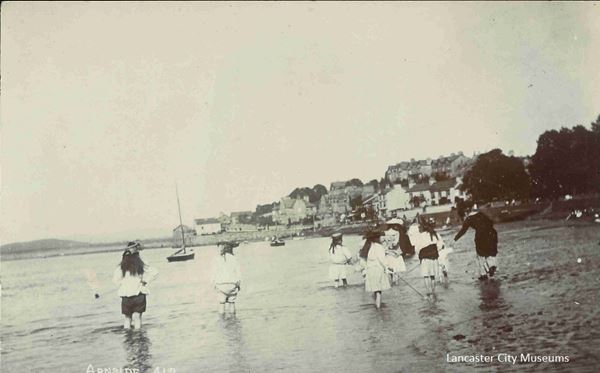

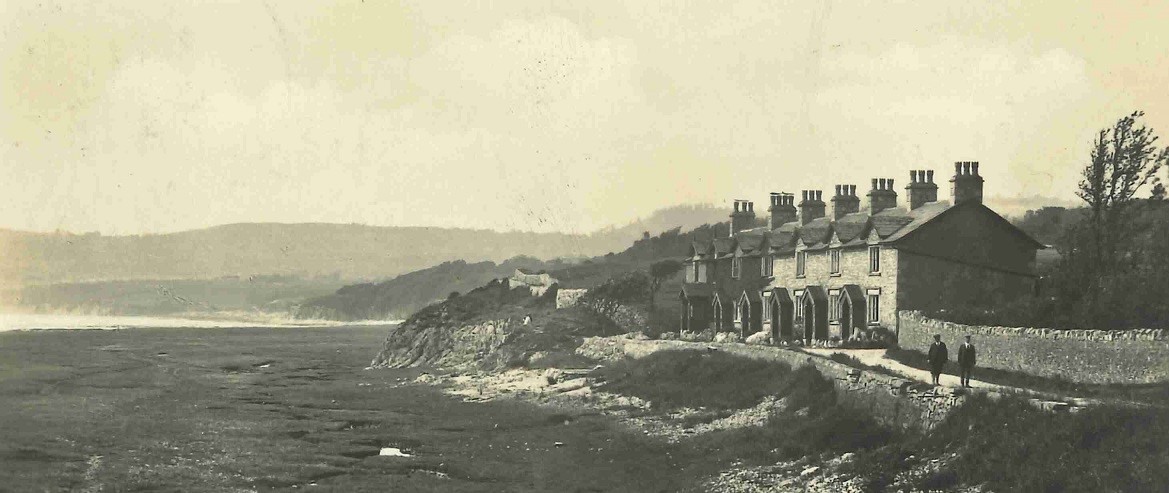

After the building of the railway in 1857, Arnside became a popular small holiday location.

Ashton

Ashton was recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Estun’. It comes from the Anglo-Saxon (Old English) æsc for the ash tree and then ‘tun’ meaning a larger settlement – possibly with an administrative function.

The Old Norse for the ash was ‘askr’, but in this case the way that the name was recorded over the years has convinced place-name specialists that it is the Old English that is at the root of the name (if you will excuse the pun).

The Ash was a very important tree in the early medieval period. In Viking mythology Yggdrasil, the Tree of Life and the World Tree, was an ash tree. They also believed that the first man ‘Askr’ was made from a log found on the shore. In British folklore the ash was connected to rebirth and new life until the 1800s.

More practically, the ash had many uses and was used in the shafts of spears, indeed the Anglo-Saxons sometimes used ‘æsc’ instead of ‘spear’.

Ashton Hall is likely to be the original site of Ashton. At its heart the Hall has a defensive pele tower built in the 1300s. These were very popular around here if you could afford them – people were no doubt mindful of the Scottish force that burned down Lancaster in 1322!

Locally, Ashton Hall is famous for having been the home of James Williamson, Lord Ashton, the ‘Lino King’. He built both the Williamson Memorial and the Town Hall.

The photo of Ashton Hall dates from around 1905 when Lord Ashton was living there.

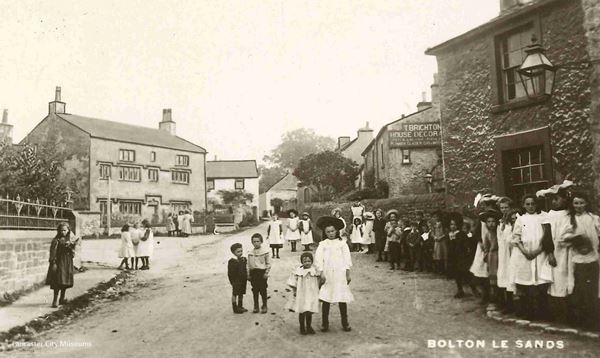

Bolton-le-Sands

Bolton was named ‘by the Sands’ and then ‘le Sands’ to distinguish it from Bolton-le-Moors – which we now know as Bolton.

Bolton-le-Sands was first recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Bodeltone’. It comes from the Old English ‘bōǷl’ meaning ‘a dwelling or house’ and is pronounced ‘bothel’. It is also turns up in Bootle (near Liverpool) and Fordbottle on the Furness peninsula.

Bolton is common in Yorkshire and can also be found in Scotland, the North-East and the North-West. The furthest south it is found is just south of Manchester. Perhaps it is connected to the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria, which also controlled parts of what is now southern Scotland.

So, it means the ‘tun’, which is a larger settlement (possibly with an administrative function), that is made up of a number of dwellings or houses.

Bolton-le-Sands was a significant place. It has an ancient parish, which was perhaps formed in the 900s. This was when the hogback stone was created – a fragment of which can still be seen in the church.

Borwick

Borwick was first mentioned in the Domesday Book as ‘Bereuuic’ with, literally, a double ‘u’.

‘Berewic’ is an Old English (Anglo-Saxon) word. Before the development of parishes and townships it is thought that much larger estates existed. Kings and nobles would travel around to estate centres and while there the estate would feed them and their retinue.

The estates would be pretty much self-contained and originally ‘wicks’ were places that specialised in something. The word ‘wick’ having come from the latin ‘vicus’ – the settlement outside a Roman fort.

A berewick was originally a place that specialised in barley and possibly brewing, as barley is the main ingredient in ale. When water quality was so poor weak ale of around 0.5% was drunk by everyone, so barley was a vital crop.

By the time of the Domesday Book the large estates had broken up and smaller estates had formed. Berewicks were now an outlying estate centre for a lord where produce was stored.

In the case of Borwick this was for the lordship of Beetham which was owned before the Norman Conquest by King Harold’s brother, Tosti the Northumbrian Earl. Borwick is unusual for being called ‘bereuuic’ as often Domesday Book gives a place name and says that the place is ‘a berewick’.

Berewicks were similar to Bartons – which mean ‘barley farm’ and could be an outlying part of the estate centre with an administrative function. Perhaps there are more ‘Bartons’ because they developed as part of the fragmentation of the larger estates?

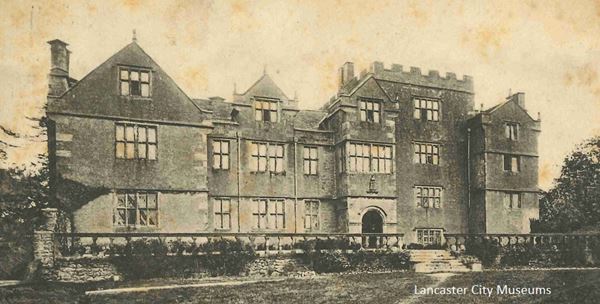

The photo shows Borwick Hall, most of which dates from the later 1500s up to the mid 1600s

Bowerham

The spelling of Bowerham is very probably a bit of Victorian up-grading. The 1844 Ordnance Survey map shows a farm called Bowrams which is likely to be the original location of the village.

Bowerham is first recorded in the early 1200s when it was Bolerund (1201), Bolron (1212) and Bolrum (1226). It was still ‘Bolron’ through to the early 1600s and Lancaster’s first recorded mayor was ‘Robert de Bolron’ in 1338.

The first part of the name is most likely to be ‘bull’ – or ‘bule’ as it was in the 1200s. The ‘run’ part almost certainly comes from the old Norse ‘runnr’ for thicket.

So Bowerham means something along the lines of ‘the thicket with the bull’. A bull was a precious farming asset and this was perhaps the place where ‘the bull’ lived over several generations. Unfortunately at this distance of time it can only be speculation.

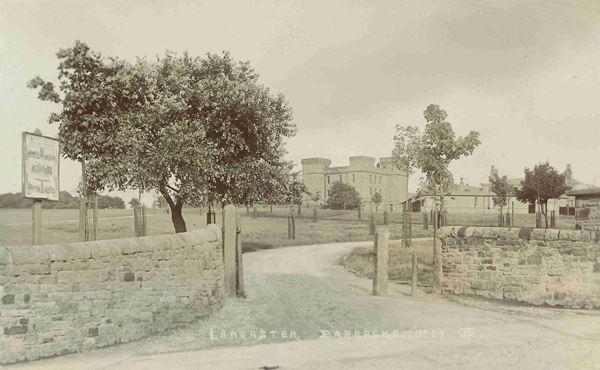

The picture shows Bowerham Barracks which was built around 1875 on the site of Bowrams farm.

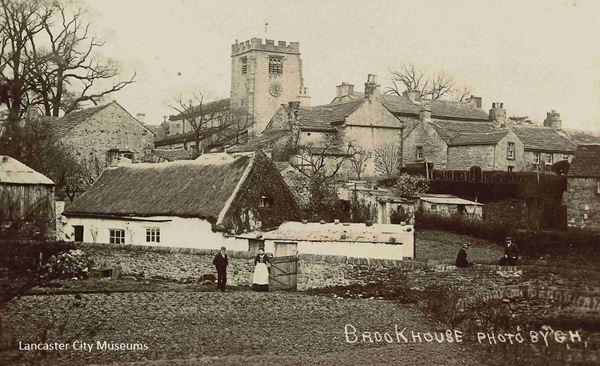

Brookhouse

It is not known when the name Brookhouse first appeared. Brookhouse is composed of two Anglo-Saxon (Old English) words, brōc (brook/stream) and hūs (house).

The first ‘house by the brook’ was probably on the site of the current Brookhouse Old Hall, which was built in 1713 beside the Bull Beck.

What is now called Brookhouse was once the centre of Caton township. Caton included several hamlets, such as Town End and Caton Green.

The old Roman road heading east from Lancaster up the Lune Valley ran by Old Hall Farmhouse near the centre of modern Brookhouse and on to Caton Green.

In the late 1700s and early 1800s the centre of Caton shifted to Town End. This was because of the nearby industrial mills and also the new turnpike road along the Lune Valley (now the A683).

So, when the Post Office decided that Caton had become too spread out for them, it was Town End that became officially Caton and the old village centre was named Brookhouse.

Bulk

Bulk is first recorded in 1318 when it was a township of scattered places and hamlets without a particular centre. These included the hamlet of Newton and also a place called Ridge ‘Rigge’.

It also included Dolphinlee, but this wasn’t recorded until 1533 when it was ‘Dolfenlee’ and ‘Dolfenley’.

It is Newton that was recorded in the Domesday Book when it was literally the new ‘tun’. A ‘tun’ was a larger settlement and later an estate. Newton may well have been a new estate formed in the Viking era as the larger estates were breaking up.

In 1094 the foundation charter for Lancaster Priory in 1094 referred to a mansion (essentially a manor house) at Newton. Newton Beck marks roughly where Newton will have been sited.

The ground rises to 280 feet along a long ridge. Bulk is thought to most likely derive from the Old Norse ‘bulki’ meaning ‘a heap’ or ‘cargo’. This became the Middle English ‘bulk’, meaning ‘a heap’.

The name probably came from the appearance of the ridge that is the defining characteristic of the township. Bulk seems to have stretched all the way to roughly where J34 of the M6 is today.

Dolphinlee comes from the Scandinavian name Dolfin and the Old English ‘leah’. ‘Leah’ originally meant a clearing in woodland, but later meant pasture or meadow.

In the late 1500s and 1600s, Bulk was owned by the Roman Catholic Dalton family of Thurnham Hall. Dolphinlee was a centre for Roman Catholicism and Mass was held there illegally.

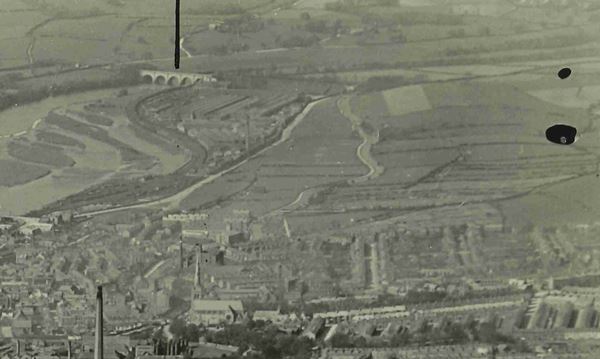

The photo shows an aerial view of Lancaster showing the slope up to Ridge to top right. Newton Beck comes out near the present junction of Langdale Road and Caton Road which is not far past the chimney (now Standfast and Barracks).

Burrow (near Bailrigg)

Although a very small place now, Burrow was first recorded around 1200 as ‘Burg’, ‘Burgo’ and ‘Burgum’. This comes from the Anglo-Saxon (Old English) ‘burh’ or ‘fortified place’.

It is near here that the amazing Roman ‘Burrow Heads’ were found that can be seen in the City Museum. Unique in this country it is thought that they came from a Roman mausoleum that would have stood near the Roman road that crosses the canal just south of Broken Back Bridge.

It has been suggested that nearby Burrow Heights is a small hillfort. This would explain the use of the specific term ‘burg’ and indeed why in 1268 it was referred to as ‘Aldeburgh’ or ‘the old fortification’. Alternatively it could relate to Roman ruins.

Unfortunately we do not have any old photos in the museum collections of Burrow. The image you can see shows the enigmatic ‘Burrow Heads’ on display in the City Museum.

Burrow-with-Burrow

As the song might have said, Burrow-with-Burrow, so good they named it twice!

Actually at Domesday in 1086 it was recorded as one place ‘Borch’ and in 1212 as ‘Burg’. Like the Burrow near Bailrigg, this comes from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) ‘burh’ meaning a ‘fortified place’.

The fortification concerned was the Roman fort based on the Roman road up the Lune Valley from Lancaster via Brookhouse, Caton Green, Claughton, Hornby, Melling and Tunstall.

The Roman fort at Burrow was also just due west of the key Roman road heading north from Manchester to Ribchester and then on to Carlisle via Low Burrow Bridge. The fort was linked with this route by a road along the north side of the Leck Beck.

The original Burrow split to be the two manors of Over and Nether Burrow. Nether Burrow is on the southern side of the Leck Beck along the Roman road. The Roman fort, along with Burrow Hall, is on the north side at Over Burrow.

If the historian John Blair is correct, then either Burrow or Whittington are prime candidates to be the ‘burh’ that Burton-in-Lonsdale served. He notes that old Roman forts are usually ‘caster/chester/cester’ unless they develop this ‘burh’ function and have a dependent ‘burh-tunas’. He defines the ‘burh’ as an ‘important node in the royal infrastructure’. In the Early Medieval period, Burrow would have been very well placed on key road and river routes.

The image shows Nether Burrow looking north heading towards Over Burrow around 1900.

Burton-in-Lonsdale

Burton was first recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Borctune’ with the ‘in-Lonsdale’ first mentioned around 1130.

The traditional explanation for a Burton is a tūn with, or near, a fortification or ‘burh’ – both from Old English. The tūn settlement in this case would almost certainly have had an administrative function.

In the case of Burton-in-Lonsdale, it was presumed that Castle Hill might be a pre-Conquest fortification. However, recent thinking is changing this view.

Early Medieval historian, John Blair, recently proposed that the ‘burh-tūns’ might not have had fortifications themselves. He argues that they developed in Mercia in the 700s and that they were part of a wider complex of sites. These sites were clustered around a royal or important aristocratic centre and formed an administrative whole.

The ‘burh-tūns’ are around 2-4 miles from the centre and are of defensive and/or administrative importance (although not necessarily fortified). They were the equivalent of an outpost – the ‘tūn’ belonging to the ‘burh’ and are often on routes or frontiers.

Blair noted that in the north-west they seem to control river valleys leading up to the Pennines. This Burton is at a crossing of the River Greta before it flows into the Lune.

So where would the centre here have been? Probably either Whittington (4 miles) or the Roman fort just across the Lune at Burrow (3 miles). Whittington itself is a type of place-name that first appeared after 760.

The important Domesday lordship of Whittington had belonged to King Harold’s brother Tosti, the Northumbrian Earl.

It helped to control the Lune Valley from Gressingham to Sedbergh via Arkholme, Newton, Whittington and Burrow (on opposite sides of the river), Casterton and Barbon.

It then also helped control the Greta valley via Cantsfield, Burton, Barnoldswick and Ingleton. The part of the key Aire Gap route (A65) between Ingleton and Casterton was covered via Ireby and Leck.

From Hutton Roof to the west and Ingleborough to the east, a watch could be kept over the wider area.

Blair remarks that Roman places that became ‘burhs’ would usually be called ‘burh’ rather than ‘chester/caster/cester’. He also observes that places called Chesterton or Casterton are often connected to Roman ‘-ceaster’ places. So, this perhaps makes it more likely that Burrow was the ‘burh’ centre that Burton was connected to, with Casterton also linked.

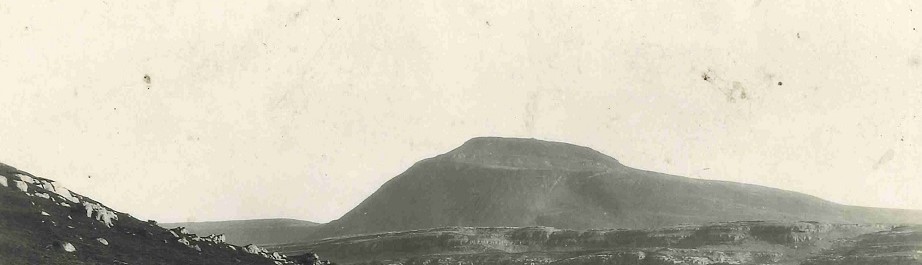

The photo shows Burton around the 1930s-50s with Ingleborough looming in the background.

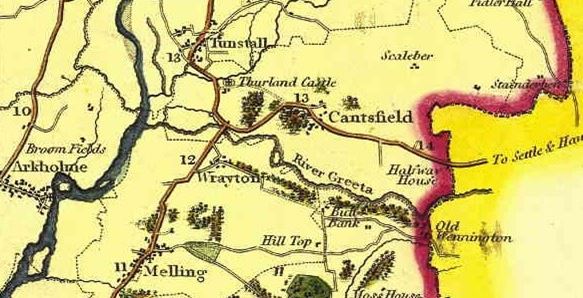

Cantsfield

Cantsfield was recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Cantesfelt’. It is a real rarity in this part of the world as the Old English ‘feld’ originally meant ‘open country’. The same word can be seen cropping up in the Dutch ‘veld’.

‘Field’ names in England are generally thought to date from the 500s and 600s. Since it is thought that the Anglo-Saxons only started to settle in this part of the world in the 600s, it is perhaps at this time that Cantsfield was named. Only from the late 900s did the meaning start to change to arable land, reflecting changes in farming practices and the break-up of the larger estates to smaller townships and parishes.

The first part of the name ‘Cant’ has been the subject of discussion. The favoured suggestion these days is that it is named after the Cant beck and that ‘Cant’ was a British (Celtic) name. Many of our local river names are British in origin due to the probable survival of British lordship in this area until around the 600s.

The other suggestion is that it is a personal name – and this was the favoured option back in 1922 when Ekwall wrote his book on the ‘Place-names of Lancashire’. Ekwall felt that it might be a shortened form of the Anglo-Saxon name Centwine and that the river was named after the place (as is felt happened with the River Wenning).

The area in the upper Lune Valley which includes Cantsfield seems to have been significant in the early medieval period. For the nature of the area there are a large number of single township parishes. Lancashire was so sparsely populated that this is why there are usually many townships to a parish as they had to be able to afford a priest and a church.

As has already been mentioned there was an important Domesday lordship of Whittington – which included Cantsfield. The area also includes the Roman fort at Burrow and was on the route through to Settle and the ‘Aire Gap’ routeacross the Pennines.

The map is taken from Greenwood’s map of Lancashire of 1818. The full map can be found here.

Capernwray

Capernwray is an unusual placename. It is first mentioned around 1200 as ‘Coupmanwra’ and in 1212 as ‘Koupemoneswra’.

The first part comes from the Old Norse ‘kaupmađr’ meaning ‘merchant’. This might mean a merchant or it might possibly be a personal name – no doubt reflecting what great traders the Vikings were. The second part is from the Old Norse ‘(v)rá’ meaning ‘corner’.

It therefore means either ‘merchant’s corner’ or ‘Merchant’s corner’ depending on whether it refers to a trader or a person. So, it might have been owned by someone called Merchant or be a place that is either owned by a merchant or possibly somewhere where merchants met to trade.

On the face of it, it seems unlikely that this is somewhere where merchants might meet to trade. However, the site of Capernwray Old Hall is not far to the north of Over Kellet (which is sited on a crossroads) and close to the River Keer – although there still seem better places to trade!

Two similar placenames can be found in the old West Riding of Yorkshire at Capon Hall near Malham and Copmanroyd near Otley (a ‘royd’ being a clearing). Then in York there is Copmanthorpe in the ancient St Mary Bishophill Junior area. Similar names are the lost ‘chapmoneswyk’ or ‘the trader’s wic’ near Peover Superior in Cheshire, between Northwich and Macclesfield. Chapman being the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) equivalent.

Capernwray seems to have been a small manor within the township of Over Kellet. The current Capernwray Hall was built in 1844 well away from the original site on enclosed common land – replacing an earlier 1805 house. At the Hall used to be a piece of a stone cross dating from the 700s or 800s, but this very likely came from Lancaster as the family who owned the Hall also owned the ‘Living’ of St Mary’s, Lancaster – today’s Priory Church.

The photo shows the current Capernwray Hall in 1907.

Carnforth

Carnforth is first recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Chreneforde’. This is Old English (Anglo-Saxon) meaning ‘Crane Ford’. No doubt the low-lying wetland in the area was perfect for cranes.

Like Scotforth, over time the Old English ‘ford’ changed to ‘forth’. This change is most common in Yorkshire with the most southerly example just south of Nottingham.

The ford was an important crossing point over the River Keer for the Roman road, which now seems to have headed via Warton and Yealand to Watercrook near Kendal. The ford was overlooked by the Iron Age hillfort at Warton.

Carnforth was likely an important crossing point in the Early Medieval period as the Roman road seems to have come up from Lancaster to the south and then headed north via Warton.

Meanwhile to the east a route (now the B6254) may already have run through to Kirkby Lonsdale to join with the Aire Gap route across the Pennines (now roughly the A65).

There was also likely to be an alternative route up to Kendal via Burton-in-Kendal as near to this road there was a district meeting place or ‘Moot Haw’ – also overlooked by Warton. This route crosses the Keer further north, so will not be the ford that Carnforth is named after.

Unfortunately the Moot Haw was destroyed by first the railway and then the M6.

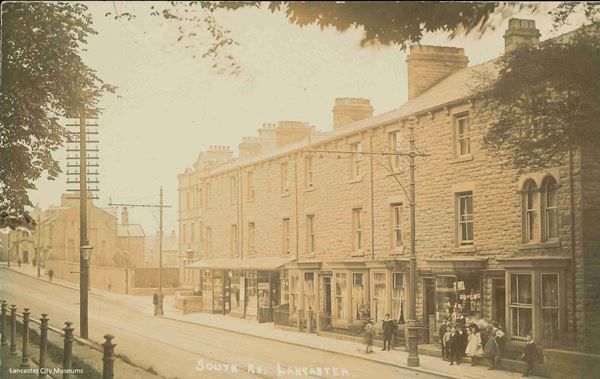

The photo dates to around 1900 and looks north up North Road – to the right is the road to Kirkby Lonsdale and to the left the road to Warton and Yealand.

Caton

Caton hasn’t changed as a name in almost 1,000 years – being spelt as ‘Catun’ in the Domesday Book. It is likely to be a good example of what are known to placename scholars as ‘Grimston hybrids’. This is when a placename has a Norse or Danish personal name plus Old English ‘tun’.

In the case of Caton, the village is probably named after a man called Kati – which is an Old Norse personal name and reflects the Norse influence on the Irish Sea region.

There are a lot of ‘tuns’ (larger settlements) that have a personal name at the start, either Anglo-Saxon or Scandinavian. They seem to have come into being from the 950s onwards when the earlier large estates were breaking up to form manors and townships. At the same time the larger areas served by the minster churches were breaking up to form parishes.

The photo shows the ‘Town End’ of the old township of Caton, which was centred on Brookhouse. It was officially named as Caton in the 1800s when the Post Office decided that the area was too big for the whole township to come under ‘Caton’.

The mill stream that runs by the Old Oak was fed from the Artle Beck further up the valley. It drove five mills at one point – Caton Low Mill (cotton), Rumble Row Mill (turning), Willow Mill (bobbin), Caton Forge Mill (bobbin) and a corn mill.

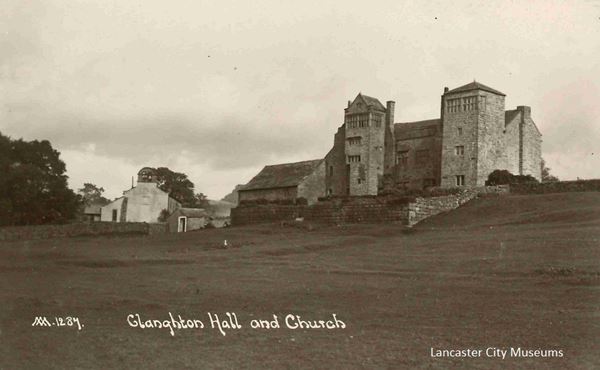

Claughton

Claughton, is written as ‘Clactun’ in the Domesday Book. It went through several spellings – as ‘de Clafton’ in 1246, ‘Clagton’ in 1255, ‘Claton’ in 1257 and finally Claughton in 1297. It is a good example of why the other Claughton near Garstang, which was ‘Clactune’ in Domesday, then Claghton in 1285, is said differently – even with the same spelling and meaning. Claughton near Lancaster being said ‘Clafton’ or ‘Cloughton’ and Claughton near Garstang being ‘Clyton’.

Both Claughtons were most likely named after the Old Norse for hill, which is ‘klakkr’, and so Claughton is probably named after Claughton Moor.

In medieval times moorland was an important part of the village economy and was used for activities like grazing, peat cutting and quarrying. Most villages and towns would have access to ‘moor’. In low-lying villages this might be some way off and the village had rights to walk their animals through to the moorland, or it might be on a flatter piece of ground that wasn’t good enough to grow crops but could be grazed by animals.

Claughton would therefore be the ‘tun’ – larger settlement (possibly with an administrative function) by the hill.

There are certainly indicators that Claughton was a reasonably important site. Around the time of Domesday Book it was a parish with only one township in it, which was unusual in this part of the world. The church also boasts the second oldest dated bell in the country at 1296.

The photo shows Claughton Hall, built around 1600, but with some parts dating back to the 1400s. The Hall is shown before it was moved to the present site and rebuilt in 1932-5

Cockerham

Cockerham is a very straightforward name which was recorded in the Domesday Book as Cocreham.

It is the ‘hām’ or smaller settlement (later the word became ‘home’) on the River Cocker.

The ‘ham’ ending was used in early Anglo-Saxon placenames. Recent research by Dave Ratledge into the course of the Roman Road north to Lancaster now shows it passing through Cockerham – making it a very likely candidate for early settlement by the Anglo-Saxons. Possibly it already existed and was just re-named. All the maps can be found here

The River Cocker was probably first mentioned in 934 as the Cocur. Like many names, particularly on the west side of the country, Cocker is likely to be a British name. If so, it means ‘crooked’ or ‘winding’ – which indeed it is.

The photo shows Cockerham in 1918 at the end of the First World War.

Dent

Although Dent is not in the Lancaster district, it has historical connections along with Ingleborough and Burton-in-Lonsdale.

Dent was first recorded in 1202-8 as ‘Denet’. There are suggestions that it came from a Brittonic (Celtic) word ‘dind’ meaning ‘a hill’ (likely Ingleborough), but also that it might be an old British river name.

However, some have suggested that Dent may be named after a British leader called ‘Dunot’. This may be the King Dunod mentioned by the Welsh Annals in the late 500s.

In the mid-670s King Ecgfrith of Northumbria granted lands to St Wilfrid’s new minster at Ripon. They included the ‘regio Dunutinga’ – ‘the region of the people of Dent’ or ‘the region of the people of Dunot’.

Dent is thought to have been an important place in the ‘regio Dunutinga’. It has been suggested that the ‘regio’ covered the area of the old Ewcross Wapentake (or Hundred) that covered Sedbergh, Garsdale, Dent, Burton and Thornton-in-Lonsdale, Ingleton, Horton-in-Ribblesdale, Bentham, Clapham, Austwick and Lawkland. However some of these places came under the lordship of Whittington in the Domesday Book when, of course, Lancashire didn’t even exist!

Based on the remaining early Anglo-Saxon sculpture and church dedications to St Wilfrid, recent work by Felicity Clark has proposed that the religious sites in the Lune Valley were influenced, if not overseen, by Ripon.

Therefore it is possible that the ‘regio Dunutinga’ also included the Lune Valley, or it may have been one of the ‘other places’ mentioned in the grant at the time. Given what good farming land the Lune Valley was, it would seem unusual not to have referred to it directly. St Wilfrid would almost certainly have welcomed its addition to Ripon’s portfolio of properties.

The photo shows the road up by Flintergill at Dent. Flintergill was first mentioned in 1610.

Dolphinholme

Dolphinholme is not recorded as a name until 1591 when the Duchy of Lancaster records show a ‘Dolphineholme’, meaning ‘Dolfin’s island or promontory’.

Holme comes from an old Norse word roughly meaning ‘island’. Rather than an island surrounded by a sea or lake it usually means a raised area of land in wet, boggy or marshy ground – Torrisholme would originally have been a good example.

However, like Arkholme in the Lune Valley, Dolphinholme is on steeply rising land coming away from a river valley – in this case the River Wyre. They both therefore are likely to come from the rarer meaning of ‘holme’ as a promontory.

Dolfin is almost certainly a Scandinavian name, however Scandinavian names were still commonly used in this area until well into the Middle Ages so all we can tell is that the name dates after 900.

Although seemingly a small rural village before the mill came, Dolphinholme’s position as a crossing on the River Wyre is significant. There is a medieval defensive motte and three Roman coins that would have been used when the Romans first came to this area were found here.

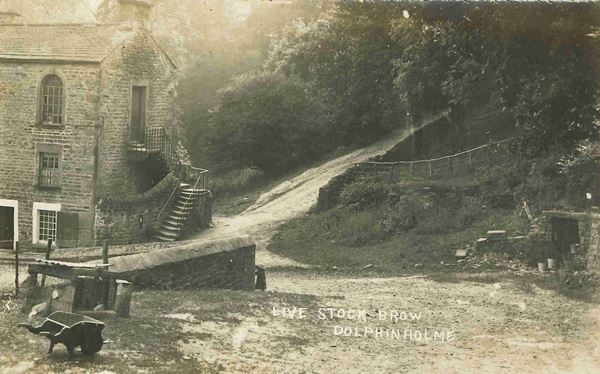

The photo shows Corless Mill at Dolphinholme.

Galgate

The meaning of Galgate is ‘the Galloway Road’ and it was first recorded in 1267-8 by the monks of Cockersand Abbey as ‘Galwaithegate’.

It has been assumed that the name originates in the drovers’ practice of walking their cattle over long distances to market. In the mid-1200s the population was booming and markets were thriving so this may well be the most likely explanation.

The practice of droving is associated with the early 1600s onwards once England, Wales and Scotland were ruled by one monarch, but it is likely to be much older. Recent research seems to show the Roman road north going via Cockerham, but by the 1200s the road had obviously shifted to run through Galgate. This was possibly due to a rise in sea levels in the late Roman and/or Early Medieval period.

Both the Lancaster area and Galloway were closely connected to Ireland and the Isle of Man in the Viking Age and had strong Hiberno-Scandinavian links. These may have encouraged greater freedom of trade within and through the area.

The ‘gate’ part does not refer to an actual gate but comes from the Scandinavian word ‘gata’ for a road. You can often see it still used in northern towns today e.g., St Leonards Gate in Lancaster. Scandinavian words were used in this part of the world well into the Middle Ages and so it does not mean that the place was named in the Viking Age.

Galgate is very quiet in this photo from the 1920s/30s, but the Shell sign is an indication of its position on the main road to Lancaster.

Glasson

Old Glasson stands on a raised area a little above Glasson Dock. It was first mentioned in 1265 as ‘Glassene’.

There are a couple of options as to what the name might mean.

It may come from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) glæs – just as Gleaston does in the Furness Peninsula.

If so then it means ‘gleam’ or ‘shining’ – possibly a reflection (literally!) of how the light shines off the water. Or maybe there was once a beacon there to help guide boats into the Lune?

Alternatively it might be something else entirely and be named from a Gaelic personal name ‘Glassán’ as in Glassonby in Cumbria. If this is the case then this is an excellent example of the close links that this area had with the Irish Sea region – particularly during the Viking Age and just afterwards.

Glasson Dock was opened in 1787 as the port for Lancaster as the Lune was now too shallow for the larger vessels that were needed.

The photo shows a view across the Lune from Overton Church to Glasson Dock. Old Glasson can be seen as the raised area to the right of the Dock and it shows how Overton and Old Glasson had the potential to be complementary high points at the entrance to the Lune.

Greaves

The Greaves just outside Lancaster comes from an Old English word ‘grǣf’ meaning ‘coppiced wood’.

In the medieval period coppicing was when trees such as oak, ash or hazel were cut down close to the ground. They then re-grew, producing fine straight growths that could be used for many items like poles, wattle fences and walls, bows and arrows.

Variants of ‘grǣf’ are ‘grove’ or ‘grave’ and it is a common element in place-names in the West Midlands and the West Riding of Yorkshire. Another name for a coppiced wood is a ‘copse’.

The word ‘grǣf’ could also become associated with the word ‘grafan’ – ‘to dig’. This happened because these groves might well be surrounded by a protective ditch to keep out grazing animals. There are therefore some places where it means ‘pit’ – such as Orgreave in West Yorkshire and Orgrave on the Furness peninsula.

Usually though it means trees and place-name specialists often look at the surrounding landscape to decide which is most likely. In this case a grove of coppiced trees would have been a precious asset worth naming.

The photo shows Greaves Road around 1900

Gressingham

Gressingham was first recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Ghersinctune’. It shows how, while some names could stay almost the same, some have changed in the intervening millennium – or were perhaps mis-heard by the scribe at the time!

Certainly by 1183 it was ‘Gersingeham’. Grassington in Yorkshire was similarly spelled ‘Ghersintone’ and both Grassington and Gressingham mean ‘grazing farm’.

Situated just up the hill from an important crossing point of the River Lune, Gressingham has some important stone sculpture dating from the 800s when this area was part of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria. The stonework identifies Gressingham as a religious centre.

The photo shows Gressingham around 1900.

Halton

Like so many names in this area, Halton was first mentioned in the Domesday Book. The name has not changed as it was recorded as ‘Haltune’.

The ‘hal’ part comes from the Old English ‘halh’ for ‘nook’, ‘valley’ or ‘hollow’ but might also be ‘low lying land liable to flooding’. As previously mentioned, the ‘tun’ means a significant settlement such as an estate or village, possibly with an administrative function. So, Halton is the larger settlement in the valley. In this case the administrative function is almost certain.

Halton was an important place in the medieval period. Halton parish was rich enough to only have one township and there is religious stonework dating from the late 700s onwards. It has been suggested that it acted as an early baptism centre before the Viking period.

At the time of the Norman Conquest in 1066 Halton was an important manor of Tostig, the Northumbrian Earl. After the Conquest a motte and bailey castle was built there, helping to guard the crossing over the Lune.

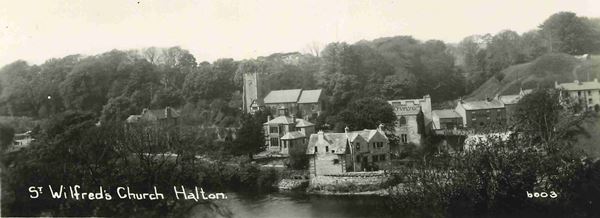

The photo shows a view across the river to the church with the castle motte to the right.

Heysham

Heysham is recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Hessam’. The first part is the Old English ‘hæs’ meaning ‘brushwood’ or ‘underwood’. It was often used in relation to swine pastures – a valuable resource in the village economy.

The second part comes from the Old English ‘ham’ which should be pronounced with a long ‘a’. This word didn’t need to change much to become our ‘home’ and also part of ‘hamlet’. It was used early on in the Anglo-Saxon era and it has been suggested that in Lancashire it often denotes an early settlement connected with the church.

Heysham was a very significant place. It has a range of early medieval religious stonework dating back possibly to the late 600s. It also appears to be a ‘double minster’ site and St Patrick’s chapel boasted some high-status wall plaster with writing (in Latin) on it.

Like Halton, Heysham parish was unusual in Lancashire as it had no other village townships within it. It was also independent of the large powerful Lancaster parish, although the Prior of Lancaster was granted the Lower Heysham part of the manor.

The lord of Upper Heysham had special duties when the lord of Lancaster entered the county. He had to meet him at the boundary with horn and staff and accompany him until he left the county again.

The photo shows the Viking-Age Hogback when it was in the churchyard.

Hornby

Hornby is first recorded as a place in 1212 as ‘Hornebi’ or ‘Horne’s -by’.

The ‘-by’ ending to a place name is Scandinavian in origin. Traditionally ‘by’ place-names have been thought of as larger, with the ‘thorpe’s being smaller, daughter settlements. However recent analysis of ‘–by’ place names in Yorkshire seems to show that they are usually located on soils more suitable for livestock than arable farming. They seem to refer to places that were originally more dispersed with many smaller centres, rather than having a main village centre.

Often from the Viking Age onwards there is a personal name associated with a place. It is thought that this can be linked to the breaking up of larger estates into smaller manors due to changes in the way that society and farming practices were organised. Horne is a Scandinavian personal name.

In the case of Hornby this will have been a replacement name for an older Anglo-Saxon settlement. We can tell this because there is religious stonework dating from the late 700s/early 800s that can still be found in the church. This re-naming happened to even important places – the famous early Anglo-Saxon monastery of Streoneshalh became Whitby.

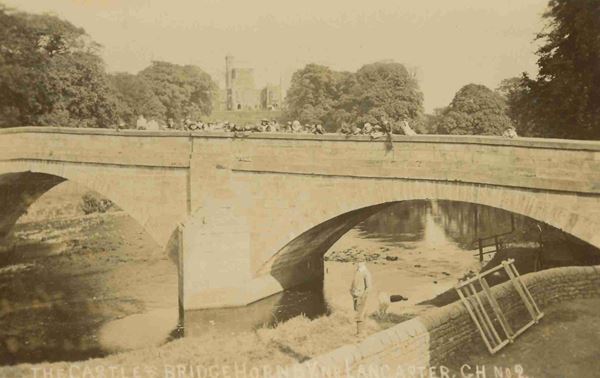

Hornby is sited at an important strategic location where the rivers Lune and Wenning meet. The photo shows a group of children on the bridge over the River Wenning around 1900. Hornby Castle is in the background.

Ingleborough

Ingleborough was first named as ‘Ingelburc(h)’ in 1165-77, although Ingleton was named in the Domesday Book as ‘Inglestune’.

Ingleborough was a prehistoric hillfort that has been described as a ‘mountain fort’. It dominates both the Lune Valley and the current A65. This road was previously known as the ‘Aire Gap’ routeway across the Pennines into the heart of the post-Roman British kingdom of Elmet (probably around the Leeds area).

The hillfort explains the ‘borough’ part of the name, from the Old English ‘burh’ or ‘fortification’. However the ‘Ingle’ part is less obvious. It is usually thought to come from the Old English ‘ing’ for ‘hill or peak’ joined with ‘hyll’ to be ‘ing-hyll’ or ‘peak hill’ emphasising the height and prominence. An alternative suggestion has been the Old English personal name ‘Ingeld’ or an Old Norse personal name ‘Ingjaldr’.

Ingleborough is one of only a few places in the country (and particularly on the west side) where houses dating from the 600s to 900s have been identified. There is a settlement site at Clapham Bottoms and one at Chapel-le-Dale by the Roman road through to Bainbridge Roman fort. There is also an enclosure site at Yarlsber that is thought to be Iron Age, but obviously had some early medieval significance as its name is ‘the earl’s (jarl’s) hill’.

Although no one would have lived on Ingleborough all year around as it is too inhospitable, it could well have been used for ceremonial purposes. After the Roman period many hillfort sites were re-occupied and Ingleborough was probably the prominent site of what became the ‘regio Dunutinga’ mentioned yesterday. If Dent does mean ‘hill’ then for them to be ‘the people of the hill’ that is Ingleborough, seems reasonable.

It is perhaps noteworthy that Yarlsber, Chapel-le-Dale and Clapham Bottoms between them cover all the main routeways up to the peak. If you walk the routes today, perhaps the most significant route feels like it might be the one from Clapham via Ingleborough Cave, the narrow gorge of Trow Gill, Gaping Gill and then Little Ingleborough, approaching via the prominent ridgeway to the summit.

Kellet (Over and Nether)

-1-v2.jpg)

Kellet is in the Domesday Book at Chellet, using the softer, Old English ‘Ch’ sound rather than the harder Scandinavian ‘K’.

It is a good example of how interchangeable these sounds could be as Kellet is Old Norse in origin. The name is an amalgamation of Kelda ‘spring’ and hlið meaning ‘slope/hillside’ (the ð has a ‘th’ sound as in ‘this’). It is the same name as Kelleth in old Westmorland, situated on the River Lune just to the east of Tebay – here the ‘th’ sound has remained. Hlið is also an Old English word but specialists can usually discern a slight difference in pronunciation to be able to tell which is which.

Kellet therefore means ‘the slope/hillside of the spring’ and there are many such springs around the Kellets, although the relevant one is taken to be a spring just below the church at Over Kellet – is it still there?

The photo shows Over Kellet in the 1920s.

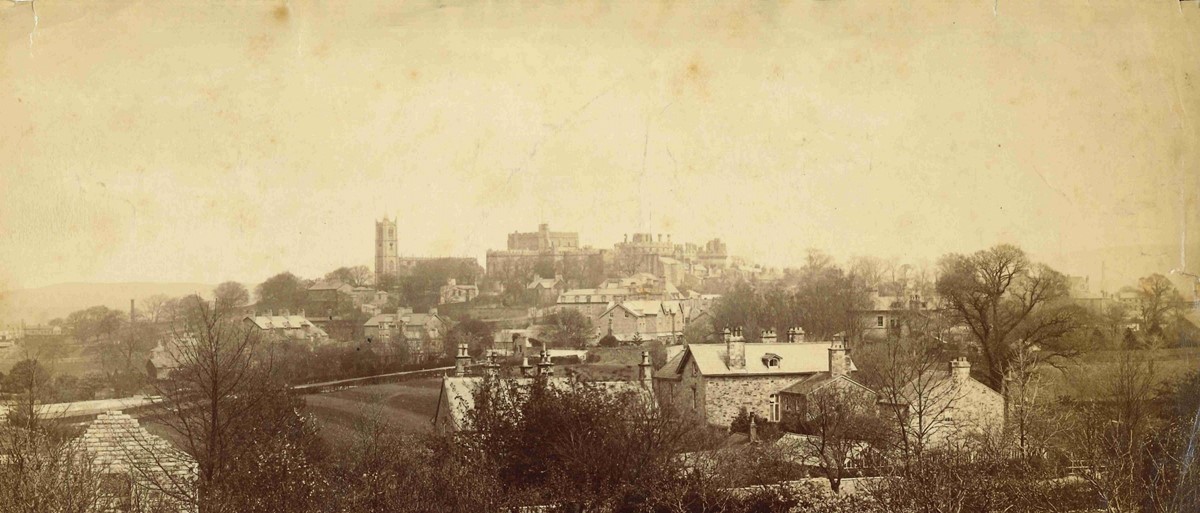

Lancaster

Lancaster literally means ‘the Roman fort or town on the Lune’. The ‘caster’ comes from the Latin ‘castra’ for military camp. It is one of a small number of Latin words that were used by the Anglo-Saxons and for them meant that it was either a Roman site or an old fortification (most usually both).

It also became ‘chester’ or ‘cester’ depending on the local dialect, but around here the hard ‘k’ sound prevailed in the end. This may well be linked to Scandinavian influence. The Welsh equivalent is ‘caer’ as in Caernarvon and Caerdydd (Cardiff).

In the Domesday Book of 1086 Lancaster was referred to as ‘Loncastre’ just as the Lune Valley was Lonsdale.

Melling

Melling’s name hasn’t changed since it was first recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Mellinge’, when it was owned by the king.

With Melling we came across another common Anglo-Saxon (Old English) place-name element ‘ing’. ‘Ingas’ meant ‘people of’, so Melling is ‘the people of either Moll or Mall’ – both names are Anglo-Saxon. The origin of the name was made even more obvious in 1094 when it was written as ‘Mellynges’.

Melling is unusual for not having a part of the name describing what type of settlement it is. For example, Mollington in Cheshire is the ‘tun’ or larger settlement of the people of Moll. It is thought that this means that Melling is an early Anglo-Saxon settlement name.

There is also a Melling in South Lancashire, just north of Liverpool. It has been suggested that these two might be connected, perhaps they were settled by the same family. If this is correct then it might show that both areas of Lancashire (north and south) were taken over by the Kingdom of Northumbria at the same time.

Our Melling was an important centre in the Lune Valley with sculpture in the church dating from the 900s. Just across the river from Arkholme, the two places were connected by a ford and a ferry. Like Arkholme it also had a Norman motte to control traffic along the Lune. Melling’s motte would also have monitored the Roman road that ran along the edge of the village.

The photo shows Melling around 1900. The motte is just to the left next to the church.

Overton

Overton is a small, yet picturesque, village today. Its historic significance can be glimpsed in its church, which was built just after the Norman Conquest.

Overton is first named in the Domesday Book as Ouretun. At first sight you might think that it refers to its position ‘over’ the River Lune from Lancaster. But the ‘over’ actually comes from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) ‘ofer’ meaning ‘shore’.

So, it is the significant settlement (or ‘tun’) on the shore.

Overton has a partner hamlet – Ortner in Over Wyresdale. Ortner is first recorded in 1323 as ‘Overtonargh’. As outlined in last week’s post on Arkholme, an ‘erg’ is probably connected to the vaccary system where large numbers of cattle were reared and managed for ploughing, meat, hides and dairy. It wasn’t uncommon in Lancashire for low-lying villages to have a separate piece of upland. This was so that each village could be more-or-less self-sufficient.

Middleton is literally the middle ‘tun’ between Overton and Heysham – again showing that these were the more important settlements.

The photo shows Overton around 1900.

Poulton-le-Sands (now Morecambe)

Poulton was first recorded in the Domesday Book at Poltune. It means the ‘tun’ (a larger settlement, possibly with an administrative function) with a pool, tidal creek or small stream – occasionally a harbour. Skippool near Poulton-le-Fylde was a harbour, or ‘Ship pool’ – from the Old Norse ‘skip’ meaning ship.

Place-name scholars have not yet worked out where the ‘pool’ part originates. It might be Old English (Anglo-Saxon) or Celtic/British – or perhaps they were inter-changeable, since the words were so similar.

Poulton was named ‘le Sands’ to distinguish it from Poulton-le-Fylde. The Sands of course being those of Morecambe Bay. Until the 1770s Morecambe Bay was not known by one name, there were several different ‘Sands’ such as Lancaster Sands, Kent Sands and Cartmel Sands.

The first person to call it Morecambe Bay seems to have been a man called Whitaker in his History of Manchester in 1771. He decided that this must be the bay named by Ptolemy around 150 AD as ‘Morikambe eischusis’ – which he described as lying between the Solway and the Ribble.

By 1889 the expanding seaside resort was officially re-named as Morecambe.

The photo shows fishermen landing mussels at Poulton (by now Morecambe) around 1900.

Quernmore

Quernmore (or as it is said locally ‘Quormer’) was first recorded in 1228 as ‘Quernemor’.

By 1342 it was ‘Quermore’ and around 1500 what looks like a bit of a departure with ‘Whermore’ – although Whernside near Dent has the same origin. On the Yates map of Lancashire from 1786 it is recorded as ‘Quarmore’ – closer to how it is said today. The current spelling makes a return to the original.

The placename derives from either the Old English ‘cweorn’ or the Old Norse ‘kvern’. Both mean ‘quern’ or ‘mill’. Quern-stones are used in hand-milling where a top stone is rotated or rolled against a bottom stone to grind grain.

They were eventually superseded by the millstone for a mechanical water, wind or animal-driven mill. The rock at Quernmore is millstone grit – a very hard stone that does not produce as much grit during milling. It was much in demand as people in the past often had teeth worn down by chewing all the grit in the flour!

The moor element comes from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) ‘mōr’. Each town or village would have some ‘moor’ for grazing their animals.

In the Roman period Quernmore was an industrial site where bricks, tiles and pottery were made. It is perhaps in the Roman period that it became so closely linked to Lancaster.

Shortly after the Norman Conquest, Quernmore became part of the Royal Forest. Like the Forest of Bowland, this did not mean that it was covered in trees, but instead was subject to the distinctive legal framework known as Forest Law. Even so, the townspeople of Lancaster had certain rights to graze their animals there. In 1278 Quernmore Park was created as a hunting park by Edmund, Earl of Lancaster, the son of Henry III.

Quernmore Park was sold by Charles I in 1630 and became one of several Roman Catholic strongholds around the Lancaster area.

The image shows the Temperance Hotel at Quernmore Brow, which was also a Post Office and had previously been the Dog and Partridge public house.

Scale Hall

Scale Hall is named after the Hall that existed at Scale, with Scale coming from the Old Norse word of ‘skali’ or ‘temporary hut, shieling’. A ‘skali’ would have been used when minding animals on the salt marsh pasture.

Scale was first mentioned in 1577 on Saxton’s map of Lancashire, although it was possibly held by a man called Thomas Travers in 1324. It was confiscated by Parliament in the mid-1600s from the Bradshaws of Preesall and Wrampool for treason during the Civil War. The present Scale Hall is a small manor house building of around 1700 with adjoining farm buildings. It is likely to be on the same site as the medieval manor house.

Scale Ford across the Lune was originally used or owned by the monks of the Priory and was referred to as Priestwath – a wath (or vað) is the Old Norse word for a ford, usually it was a tidal crossing that would involve crossing salt marsh, mud flats and river channels.

From around the First World War there was a small airfield at Scale Hall where the current Grosvenor Park housing estate sits. It seems to have gone out of regular use probably just before the Second World War. Scale Hall was also used for the Royal Lancashire Agricultural Show in 1925.

The photograph shows the front of Scale Hall in 1889 – rather smarter than the sides and back!

Scotforth

Scotforth was first named in the Domesday Book as ‘Scozforde’. The ford was no doubt over the nearby stream.

The spelling was ‘ford’ until at least 1323 but by 1501 it had changed to ‘forth’, with the Old English ‘d’ getting replaced for the softer ‘th’ . This may well have been as a result of the Scandinavian influence on how English was spoken in the medieval North.

The ’Scot’ or ‘Scoz’ part is again Old English and, like Galgate, probably indicates that this was the main route to and from present day Galloway and Scotland.

The photo shows Hala Road at Scotforth around the 1890s.

Silverdale

Silverdale was first recorded in 1199 as ‘Selvedal’ and then in 1246 as ‘de Sellerdal’.

The name means ‘silver valley’ from the Old English ‘siolfor/seolfor’ or the Old Norse ‘silfr’. Then either the Old English ‘dale’ meaning ‘main valley’ or the Old Norse ‘dalr’ meaning long valley’.

The ‘silver’ most likely refers to the pale grey of the limestone rocks – there is a Silver Hill and Silverdale in the limestone country just north of Settle. The finding of the Viking Age silver hoard, now known as the Silverdale Hoard, may be pure coincidence – although a complete gift for the writers of newspaper headlines.

For a long time the village didn’t really have a centre, with farms scattered around. It is noted for the number of large wells, some of which have never been known to run dry. Since Silverdale was very likely on the drove route for cattle across the sands the wells would have been very useful for watering the animals.

As with other areas of Morecambe Bay, Silverdale became known for its healthy sea-bathing, particularly amongst the middle classes. The first mention occurs in 1835 and the famous novelist, Elizabeth Gaskell, stayed here several times in the 1850s. It seems to have been around the end of the 1860s that the sea-bathing ceased to be an attraction.

The image shows the cottages at The Shore. The far cottage was originally the only building and was a Bath House connected to the Britannia Hotel in the village centre.

Skerton

Skerton is an old settlement that was named in the Domesday Book as ‘Schertune’. Again the Anglo-Saxon ‘sch’ sound has been swapped for the harder Scandinavian ‘sk’.

The start of the name comes from the Old Norse ‘sker’ (the Old English equivalent is ‘scar’) meaning ‘a bed of rough gravel or stones’. So, the meaning is ‘the larger settlement or village at the ayre or gravel bank’.

That part of the River Lune is well supplied with gravel banks, so the one that Skerton was named after more than 1,000 years ago may have been built over or disappeared a long time ago.

Skerton of course is on the north side of the Lune close to the crossing point at Lancaster. Old Skerton is not directly opposite Lancaster but slightly upriver.

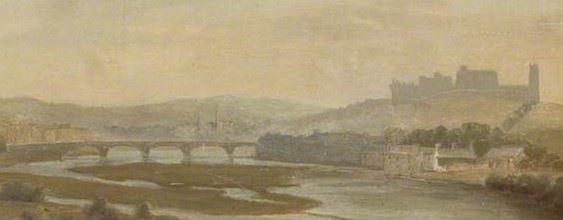

The picture shows a section taken from a painting of around 1830 shows Skerton and the gravelly nature of the Lune. Although the castle looks directly behind Skerton it is on the other side of the river as this section taken from Yates’ map of 1786 shows.

Slyne

Slyne preserves a very early Anglo-Saxon name for a slope. In the Domesday Book it was referred to as ‘Sline’, so it is likely to have been said in roughly the same way for well over a thousand years. It comes from ‘slinu’, the Old English for slope.

Although not particularly steep, Slyne is on a ridge and the old Slyne Manor House is on a slope. Slyne is on the A6. At this point the road largely follows the course of the probable Roman Road from Lancaster to Watercrook near Kendal.

This old photo of Slyne shows the gentle slope on which it sits.

Sunderland Point

Sunderland Point was probably first recorded in 1246 as ‘de Sinderland’ and then in 1262 as ‘Sunderland’

This is not an uncommon name and it very much means what it says on the tin. It is Old English (Anglo-Saxon) meaning ‘separate or detached land’.

This might not necessarily be geographical – monastic lands might be viewed as ‘detached’. However in the case of Sunderland Point it is clearly detached, or sundered, twice a day by the tide.

Sunderland Point has an interesting history. It was developed as a port from around 1680 and particularly in the 1720s. The port and the boat building failed completely once Glasson Dock opened in 1787.

But by the early 1800s the village was competing with nearby Poulton, Heysham and Hest Bank for its sea-bathing, with two inns and a bathing machine. However, by around 1830 Poulton was outstripping the others and Sunderland Point returned to being a farming and fishing village.

The photo shows Sunderland Point around 1900. The tree was said to be a cotton tree, although others say that it was a Kapok tree from the West Indies. Whatever it was, it was almost certainly brought to Sunderland Point as a result of the transatlantic trade. Blown over in 1998, it’s stump still remains.

Tatham

Tatham was first recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Tathaim’.

The name comes from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) personal name ‘Tāta’ and ‘hām’ – which was the Old English for a smaller settlement, or ‘home’. In this case the ‘hām’ has been altered to the Old Norse ‘heimr’, also meaning ‘homestead’.

Tatham is a fascinating place. It is an ancient single township parish – which again is very unusual in Lancashire generally, but less so in the Lune Valley area. The church was mentioned in Domesday and the present church has some parts dating back to the 1100s.

The local historian, Mary Higham, argued that in the North-West the ‘hām’ ending often indicates an early religious site and was similar to the ‘llan/lan’ sites of Wales and Cornwall.

At Tatham the church is in a curvilinear churchyard in land between two Roman roads. Also at one point it was probably right on the edge of the River Wenning. Taken together, these can indicate a possible early religious site. Mary Higham even suggested that it might be a British site that was taken over by the Anglo-Saxons in the 600s.

In 1086 at Domesday Tatham was part of the lordship of Bentham. The church was strangely tucked away in a little corner on the other side of the river from most of the parish. The ancient manor was named Robert Hall after Robert Cansfield, who inherited it in 1515 aged 3 years old.

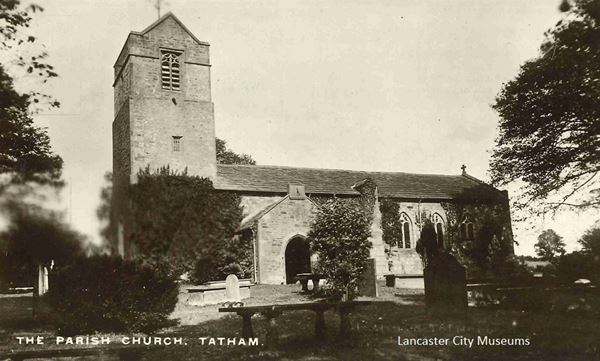

The images dates from the early 1900s and shows Tatham parish church, which mainly dates from the 1400s.

Thurnham

Thurnham is mentioned in the Domesday Book as ‘Tiernun’ and ‘Thurnum’ in 1160.

Like Arkholme, this name is not quite what it seems and like Arkholme (or Ergune as it was at Domesday) the ending means ‘at the’. In the case of Thurnham it is place ‘at the thorn-bushes’. This comes from either the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) or Old Norse ‘Ƿyrnum’ – with the Ƿ said as ‘th’.

Local historian Mary Higham speculated that in the case of Thurnham this might indicate a source of thorn bushes for building enclosures – Domesday records that such activities were going on further south in what is now Lancashire.

Close by Thurnham and Cockerham is the hamlet of Hillam, which was recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Hillun’. This comes from the Old English ‘at the hills’ and seems to be at the end of an important route across the sands from Pilling where you could join the Roman road nearby at Cockerham. In this low-lying landscape ‘at the hills’ is definitely subjective!

Mary Higham also speculated that there seemed to be a connection between these ‘at the’ sites and Roman roads and wondered whether they might indicate an early post-Roman settlement site.

The photo shows Thurnham village around 1907-9.

Torrisholme

Like so many places in this area, Torrisholme was first recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Toredholme’.

Both parts of this place-name are Scandinavian. The second part is the more usual use of ‘holme’ as a raised area, or island, in wet ground.

The first part is a person’s name, Ƿóraldr, which would be said ‘Thorold’. So Torrisholme is ‘Thorold’s area of raised ground’.

Torrisholme is situated at the end of a ridge which also has a Bronze Age barrow. Historically it was in the same township as Poulton (now Morecambe) and Bare. For around 300 years from the 1200s Lancaster Priory had a monastic farm, known as a grange, here.

The photo shows Torrisholme around 1900.

Tunstall

Tunstall was first recoded in the Domesday Book at ‘Tunestalle’ is quite a common name and is found across the country. It is an Anglo-Saxon name from the Old English ‘tūn’ (settlement) and ‘steall’ (place). It is taken to mean ‘site of a farm’ or ‘farmstead’.

The apparent humbleness of the name masks the early importance of Tunstall, which is on the Roman road heading from Lancaster up the Lune Valley to the nearby fort at Burrow.

In 1066 it was unusual in Lancashire as it was at the centre of a small parish with a church. At this point Tunstall was one of four manors attached to Bentham and held by Ketil, which is an Old Norse name. The other three manors were Wennington, Tatham and Farleton. By the later 1100s Tunstall was part of the lordship based on Hornby and ownership of the parish was given to Croxton Abbey in Leicestershire.

The village was dominated by nearby Thurland Castle.

The image shows Tunstall village in the early 1900s.

Warton

The place-name ‘Warton’ is essentially unchanged since the Domesday scribes wrote it as ‘Wartun’.

The name Warton has Old English (Anglo-Saxon) origins. It means the ‘tun’ by the guarding place or ‘Weard’. ‘Weard’ is also at the root of Ward and Warden. Warton is overlooked by the Iron Age hillfort on Warton Crag which has commanding views across Morecambe Bay. If you look you can see Warton Crag from many places in the District.

‘Tuns’ were settlements of some consequence (although we would consider them to be very small). The word later became ‘town’ although the medieval village township probably gives a better idea of relative size. Tuns are generally thought to date from the 700s onwards and may have had an administrative function. In the case of Warton this is very likely.

Warton of course remained as a site of significance and was a very wealthy medieval parish. The remains of the medieval rectory can still be seen there.

Wennington

Wennington is a very interesting place name. It is actually recorded twice in the Domesday Book as ‘Wennigetun’ and ‘Wininctune’ when it was part of lands associated both with Bentham and with Melling and Hornby. Both landowners before the Norman Conquest had Scandinavian names – Ulf (Melling and Hornby) and Ketil (Bentham).

Wennington sits on the River Wenning and the obvious thing to assume is that it is named after the river. However Old Wennington is much closer to the River Greta on the Roman road heading north from Ribchester to Burrow just before it crosses the Greta. In 1227 it was called ‘Old Wenigton’ – so 800 years ago it was considered to be ‘old’! Probably one of the Domesday landowners had Old and one ‘Nether’ Wennington. By 1499 Old Wennington was an eighth part of the manor of Wennington.

It is most likely therefore that Wenning means ‘the people of Wenna’ and so Wennington is the ‘tun’ or larger settlement (possibly with an administrative function) of the people of Wenna. The people living on the land between the Greta and the Wenning would be ‘the people of Wenna’ and the river was named after them – rather than the other way around.

Wennington became part of the lordship of Hornby and for 300 years from 1360 the manor was owned by the Morley family. In the early-mid 1600s the Morleys were fined huge sums of money for being Roman Catholics and also fighting for King Charles I. They eventually sold the estate in 1674.

The image shows the village around 1900-1910.

Whittington

First recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Witetune’ and in 1212 as ‘Witington’.

It comes from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) and means the ‘tun’ of the people of Hwīta. Hwīta was an Anglo-Saxon name and the ‘ing’ is short for ‘ingas’ or ‘people of’. A ‘tun’ of course was a larger settlement, possibly with an administrative function. These ‘ington’ place-names seem to have appeared after around 760.

It is very likely that Whittington had an administrative function because in 1066 it was the centre of an important lordship. It had been owned by King Harold’s brother, Tostig, the Northumbrian Earl, but by Domesday was under the King. A small motte still exists to the west side of the church. The lordship consisted of nearby Newton, Thirnby, Arkholme, Gressingham, Hutton Roof, Cantsfield, Ireby, Burrow, Leck, Burton-in-Lonsdale, Barnoldswick, Ingleton, Casterton, Barbon and Sedbergh.

The lordship controlled key strategic routeways. It helped to control the Lune Valley from around Gressingham to Barbon and the routes alongside the River Greta and the Leck Beck. These rivers and roads connected the Lune Valley with the ancient ‘Aire Gap’ route across the Pennines – now roughly the A65.

With a lordship of this size it is very likely that the parish church already existed. It is again a parish with a single township, which in this part of the world, indicates its prosperity and its likely early importance.

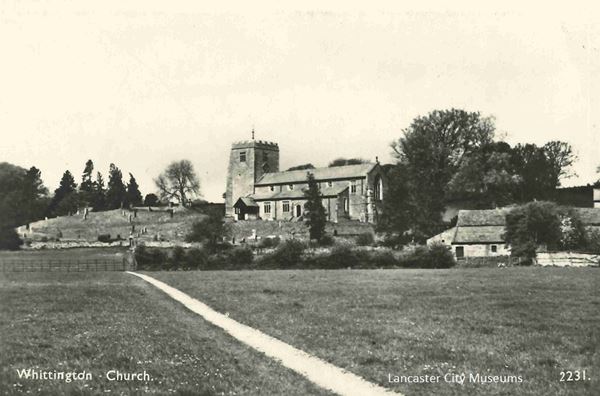

The image shows Whittington church, strategically sitting on the edge of the rise that overlooks the main road and the flat land down to the River Lune. Next to it on the left is the slight rise that is the remains of the Norman castle motte.

Wray and Wrayton

Wray is first mentioned in 1227 as ‘Wra’ and comes from the Old Norse Vrā, meaning ‘corner’. Wray stands in a corner where the Rivers Hindburn and Roeburn join.

Wrayton is first mentioned in 1229 as ‘Wraiton’ and is near a sharp bend in the River Greta. As a ‘tun’ or larger settlement, Wrayton may have had an administrative function. It is sited near the important bridge over the Greta, just before the road crosses the river before dividing to go to either Kirkby Lonsdale or alongside the Greta to Burton-in-Lonsdale.

If this was the case then Wrayton would have helped to monitor traffic going up and down the valleys of the Lune and Greta. Both connect with the important ‘Aire Gap’ crossing of the Pennines – now the A65.

The photo shows Wray between 1905 and 1910.

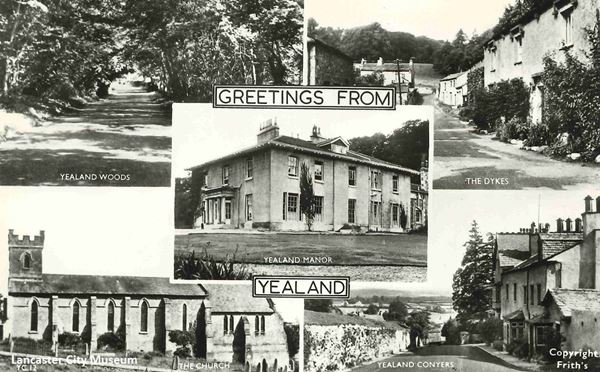

Yealand

Yealand was recorded in the Domesday Book as ‘Jalant’ (presumably with the ‘J’ said as a ‘Y’) and as ‘Yaland’ in 1206, but ‘Hielande’ in 1202.

The places that are now Yealand Redmayne, Yealand Conyers, Yealand Storrs and Leighton were all part of the original estate. In 1066 this was held by King Harold’s brother, Tostig, as part of his lordship of Beetham. ‘Yealand Coygners’ was first recorded in 1301 and ‘Yealand Redman’ in 1341 – both named after the estate owners.

There are two possible meanings depending on whether the name means ‘high land’ from the Old English (Anglo-Saxon) ‘Hēaland’ or ‘land by the stream’ from the Old English ‘Ēaland’. In his 1922 book on the Placenames of Lancashire, Ekwall preferred the ‘high land’ option.

So, how did we end up with four places from one estate?

The first split occurred in the late 1100s when the estate was partitioned into what became Yealand Redmayne and Yealand Conyers. ‘Redmayne’ or ‘Redman’ was adopted as a surname by the owner of the Yealand Redmayne estate around the 1180s and an heiress of the other part married a Robert de Conyers and they inherited that estate around 1235-45. Around 1350 Yealand Redmayne was then divided again by two co-heiresses into Yealand Redmayne and Yealand Storrs. Yealand Conyers at some point split again and the Leighton Hall estate became separate.

Recent research indicates that Yealand was on the Roman road north from Lancaster to Kendal (Watercrook) – either via Leighton or Yealands Conyers and Redmayne. The two possible routes re-join at Yealand Storrs to go on via Beetham.