The Old Bridge

If you've visited Lancaster, you've probably been to Bridge Lane - but you may not be aware of it.

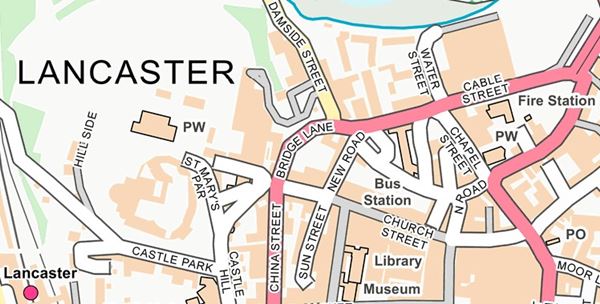

This short, steep stretch of the A6 runs down the hill from the end of China Street to the corner of Cable Street and Damside, near the bus station. Most of us - sitting in traffic on the one-way system, or taking our lives in our hands crossing the road on the blind corner at the foot of the hill - have probably never noticed the name, let alone stopped to wonder why it’s called Bridge Lane when there is no bridge in sight.

To find the answer we need to go back in time. For most of Lancaster’s long history, the lane bent to the left halfway down the hill. (A trace of this old route remains in the pedestrian underpass beneath the access ramp to the multi-storey car park.) From there it ran past what is now the Three Mariners pub, all the way down to the river and at last to the bridge for which it was named.

.png)

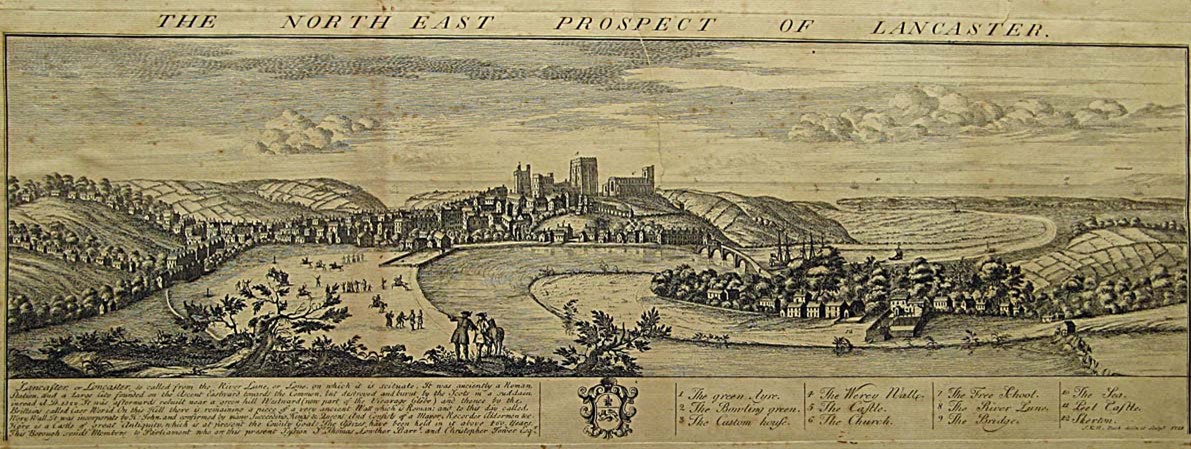

This bridge stood close to the location of the modern Millennium Bridge. For thousands of years, this area was the only place to cross the River Lune within Lancaster. The river near here was fordable at low tide, forming a crossing point that would have been used by local people long before records began. The Romans were probably the first to build a bridge, giving troops from their fort on Castle Hill easy access to the north bank of the river. Unfortunately there are no surviving records to pinpoint the location of a Roman bridge, and even the course of the river itself may have been different in this period. The first written records we have date from much later. Documents from 1215 onwards mention several royal grants of timber for the bridge's upkeep - suggesting that the bridge of this era was built mainly out of wood. It crops up in other records too, showing that it was well used and maintained. On at least half a dozen occasions over the next couple of centuries, temporary tolls known as 'pontage' were levied for periods of several years at a time to pay for repairs.

At this time the bridge was usually called the Loyne Bridge, or simply the bridge at Loyncaster. (Loyne and Loyncaster are just older versions of the names of the River Lune and Lancaster.) There's no record of when the wooden bridge was rebuilt in stone, but plenty of later images show that the new design was typical of the late middle ages, around 1300-1500. It was this stone bridge, surviving for centuries, that eventually came to be known as the Old Bridge.

Standing at the heart of Lancaster and as a key part of the primary north-south road through the west of England, the bridge must have been the site of any number of dramas over the ages, but only a few have come down to us through history.

In 1652, not long after George Fox founded his Religious Society of Friends (the Quakers) and began preaching across the North-West, he caused so much controversy amongst the religious and political establishment that he was not only accused of blasphemy and brought before the court at Lancaster Castle, but an irate crowd also threatened to throw him over the side of the Old Bridge.

During the Jacobite Rising of 1715, the bridge itself was briefly threatened with destruction in an effort to delay the Jacobite forces that were advancing from the north. But the townspeople objected, pointing out that the army would still be able to cross the shallow river by way of the ford. In the end only parts of the parapets at the northern end of the bridge were demolished. The Jacobites passed quickly through the area and were defeated shortly afterwards at the Battle of Preston.

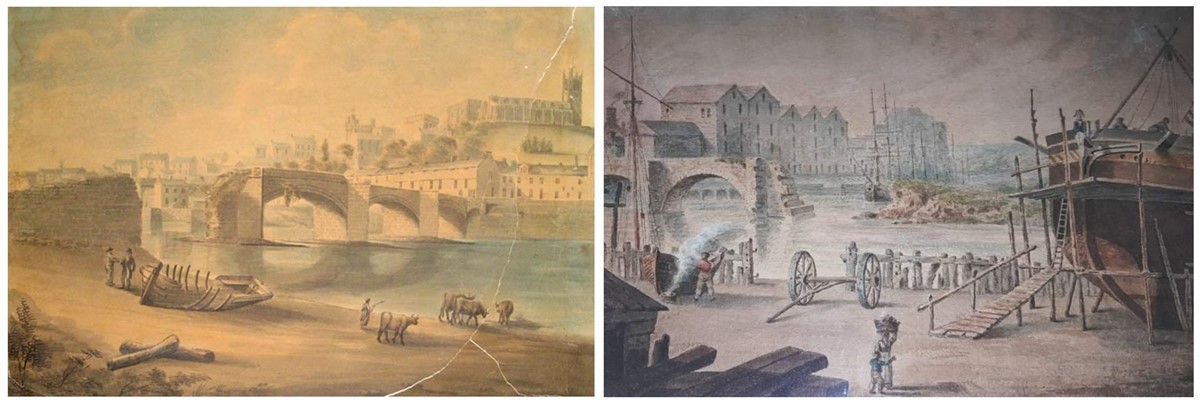

Most surviving depictions of the bridge date from some time after this incident, and show it intact except for these damaged parapets. Why they were never repaired is unclear; it certainly caused a few problems. The 18th century was a period of rapid growth in Lancaster, and traffic over the river was increasing dramatically. The narrow medieval bridge with its missing parapets became the scene of frequent accidents. One woman with a horse-drawn cart full of coal fell from the bridge after a wheel came off her cart. She was badly injured and her horse was killed. Another carter was lucky to escape injury when he landed in the water after a similar accident in the same year. A seaman named John Gregory fell to his death a few years later, while a six-year old boy survived a fall onto sand that had collected on one of the bridge's piers.

Despite its dangers the Old Bridge was a popular subject for local artists in the Georgian era. The paintings shown here are just a few of those in our collection.

In 1782 an act of Parliament was passed to allow the construction of a new bridge further upstream, to replace the crumbling Old Bridge as Lancaster's main crossing point over the river. Designed by Thomas Harrison, this elegant Georgian structure was completed five years later and is still in use today. It was known at first simply as the New Bridge, before gaining its modern name of Skerton Bridge.

The Old Bridge remained in use for a few more years, until its history took a strange turn. In 1802 it was sold to John Brockbank, who owned a shipyard a short distance upriver. He promptly had the northern arch of the bridge demolished so that his newly built ships could pass downstream complete with masts and rigging. Until that point his business had been hampered by the need to tow each hull under the low bridge and step the masts at a different site further down the river. Removing the obstacle of the bridge would also have made it easier for incoming cargoes of timber and other supplies to be delivered directly to his shipyard.

LEFT: View of the Old Bridge, Lancaster, c.1805, Gideon Yates.

RIGHT: Brockbank's Shipyard, Lancaster, c.1806, attributed to John Emery.

After the removal of the first arch, nature was allowed to take its course with the rest of the bridge. The second arch on the northern (Skerton) side collapsed only five years later in 1807, under the pressure of heavy autumn floods. In February 1814 the combination of a hard winter and a high spring tide saw the arch at the opposite end of the bridge beside St George's Quay damaged by floating chunks of ice, said to be as much as 16 inches (40cm) thick. This put the adjacent road at risk, so the damaged arch was taken down and a wall built in its place to shore up the quayside and the remains of the bridge.

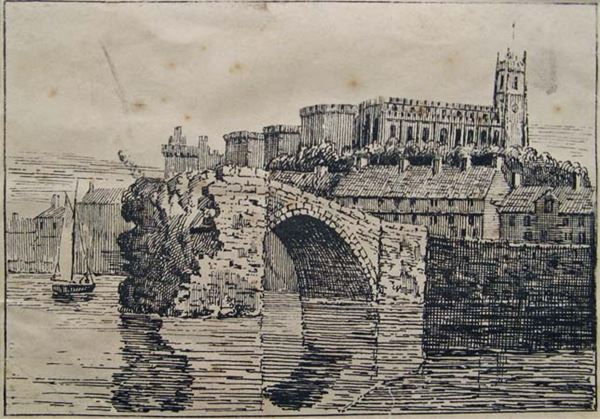

Shorn of its original purpose, local people still found uses for the raised area on top of the truncated bridge. Reports from around 1820 suggest that the space was used as a sort of civil court, where commercial disputes and other cases could be heard in public. The picturesque ruin continued to attract attention from artists too, and the story of its gradual decay emerges in a series of paintings, drawings and engravings.

At some point in the next quarter of a century, the connection between the quayside and the last arch must have fallen down or been demolished, as the last few paintings of the bridge show a single isolated arch standing sentinel in the river. This finally collapsed at 5am on the 29th December 1845. The timing was lucky, since children often played on the ruins during the day. But in the early morning no-one was near enough to be in any danger, and there was only a single witness to the demise of this last bastion of the Old Bridge.

Almost two centuries later though, some traces do remain. If you look over the side while crossing the Millennium Bridge, you might be able to make out some of the foundation stones embedded in the mud. The Old Bridge is immortalised in art and history, and even in our language; visit Skerton and you might hear the locals refer to the area at the bottom of Lune Street, where the bridge once stood, by the telling nickname of 'down Old'.

Much of the information in this article comes from books available in the reference section of Lancaster Central Library, including:

- The Making of Lancaster, George Howson

- Time Honoured Lancaster, Cross Fleury

- Lancaster, A History, Andrew White

- A History of Lancaster, ed. Andrew White

- Lancaster, A History and Celebration, Robert Swain

All images are copyright Lancaster City Museums, unless otherwise stated.