The Personal Diary of Dr. Buck Ruxton, 1934

My evening coffee tasted sharp. I inadvertently told Isobel that my coffee was peculiar in taste at the bottom of the cup. Soon after taking it, I felt giddy. She left me alone in the house. I vomited the whole night.

Isobel deliberately put liquid Morph Hydrochloride in my coffee as I found my pupils pinpoint soon after drinking the coffee.

- Saturday 24 November 1934, Diary Entry, Buck Ruxton

There are some objects within museum collections that sit brooding in their boxes, heavy with dark histories, yet so intertwined with the culture and folklore of the local community that museum curators shuttle backward and forward in their decisions on whether to exhibit them or not.

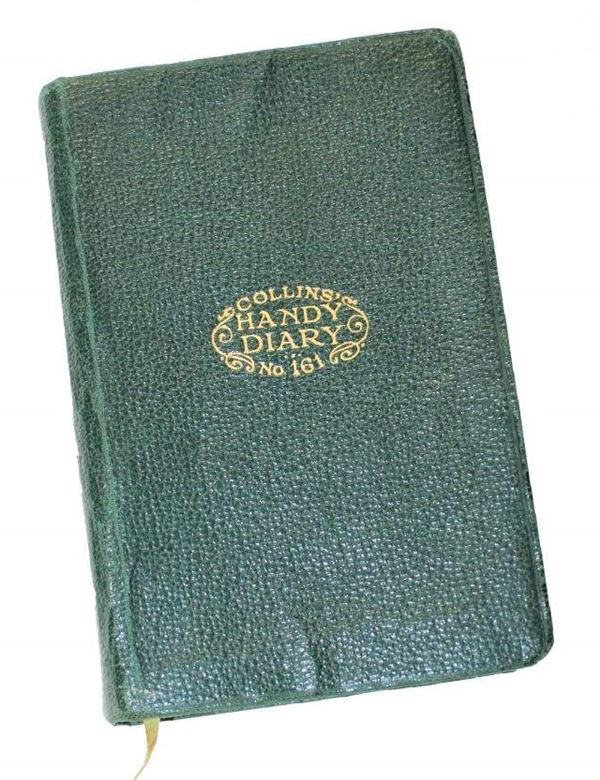

The small green pocket diary from 1934, which sits wrapped in tissue paper in an unremarkable brown box in our stores is one of those objects.

It is the personal pocket diary that belonged to Dr. Buck Ruxton, Lancaster’s notorious murderer. It contains diligent details of his personal life the year before murdering his common-law wife, Isabelle van-Ess (34), and their young maid Mary Rogerson (20).

Buck Ruxton, formerly Bukhtyar Rustomji Rantanji Hakim was born in Bombay in 1899 to a Parsi family. He studied medicine at the University of Bombay where he graduated with a Bachelor of Surgery. Ruxton went on to serve with the Indian Medical Corps in Iraq and undertake further experience as a doctor in London. After moving to Scotland, he studied at the University of Edinburgh, where he failed his examination to become a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons.

In 1930 he took over a sizeable GP practice at 2 Dalton Square, Lancaster, which tended to a large population with very disparate social wealth. Ruxton had experienced the extremes of the social class systems of India and was all too aware of how hard it was for poor people to access medical care. There were many people in Lancaster working in factories and mills with little income and Ruxton would soon develop a relationship with his patients and a reputation for being kind and caring – waiving fees for those who were struggling to pay their medical bills (remember, this was before the NHS).

Ruxton was accompanied to Lancaster by his common-law partner Isabella van-Ess (nee Kerr), whom he met in Edinburgh while she was still married. They went on to have three children.

Ruxton begins writing in the diary on 27 March 1934, which he notes as his birthday. There is nothing written prior to this date, so we can perhaps assume that it was maybe a birthday present or a thus-far unused Christmas present. Nothing remarkable about that, however, all other records cite Ruxton’s birthday as 21 March.

We can read throughout the diary about the mercurial relationship between Ruxton and Isabella. He calls her “My Beloved Belle” in the entries where he is journaling a happy event or incident. When he is upset, he calls her Isobel. He writes that she affectionately referred to him as her ‘Bonnie’. The tension between the couple is picked up in several entries, where Ruxton refers to her ‘affairs’ with someone only named ‘S’, with whom she had lived for a week. He also writes about her friendship repeatedly with ‘B’ or Bobby. It is clear from his entries that Ruxton does not trust his partner and feels that she brandished her friendship with Bobby to upset him.

“Come on Bobby we are going to the Palace Cinema” she uttered these words whilst asking Bobby to go with her, in my presence.

- Tuesday 20 November 1934

One other theme that runs through the diary entries is that of money: spending it, borrowing it, winning it and losing it.

Belle had hoped to open her own Murphy’s betting shop and Buck had rented a shop in Blackburn for her, but this never happened. Betting remains a thread through the financial entries.

Windsor Lad I (Maharaja ?)

Easton II (Lord Wooler?)

Columbo III (Lord Stanley?)

Backed horses for £122 on the Derby Day. Isobel’s suggestion about a certain horse called Medieval Knight drove me crazy. I changed my horse (Easton) to Isobel’s suggestion and lost all money except £5.

Total loss £117

Best lesson taught in my life.

- Wednesday 6 June 1934

Prior to this, Ruxton details all the items that he has bought for the living areas of 2 Dalton Square, which was furnished incredibly lavishly. This includes marble statues of the Prince Consort and Queen Victoria and a Rosewood Cabinet from the Clifton Hall sale (2 May), and a statue of an Indian slave girl holding a torch, Dresden chinaware, and all manner of silver and silk from the Hest Bank Lodge sale (26 May). He also mentions a chandelier that he saw in Edinburgh, which he asked someone to go back to buy for him the next day (21 May).

After the loss on the Derby Ruxton must have been concerned about his extravagant purchases a few weeks before and he turns to his friends for help. He asks a Mrs Webster for a loan of £100 the day after the Derby. She must have said no, as at the back of the diary he lists her as “not true blue”. On Friday 8 June a friend lends him £33. He lists them as “really good”.

It is difficult to ascertain whether Ruxton was writing purely for himself, assuming that no one else would read his diary, or whether this diary was hastily written following the murders, building the picture of a much-maligned man; a victim of potential poisoning, a loving partner emotionally abused, a kind and generous provider. Why is his birthday date different? Why did he not report the alleged poisoning? The diary throws up many questions, the answers to which we will never know.

It is difficult to ascertain whether Ruxton was writing purely for himself, assuming that no one else would read his diary, or whether this diary was hastily written following the murders, building the picture of a much-maligned man; a victim of potential poisoning, a loving partner emotionally abused, a kind and generous provider. Why is his birthday date different? Why did he not report the alleged poisoning? The diary throws up many questions, the answers to which we will never know.

What we do know is that the year before the horrific murders, and despite outward appearances, Ruxton was showing paranoia, convinced that his wife was trying to poison him, leave him, and have him arrested. He was financially struggling, borrowing money and losing money on the horses. He was burning with jealousy over his wife’s friendships with other men and all the while trying hard to maintain a prominent and respected place in society.

Even today, despite the despicable and brutal murders of two women, there remains a curious tenderness for Ruxton, who is still referred to as a physician for the working classes and a kind and gentle man.

The details of the case are widely available online, where you can find out more about the murders of Isabella and Mary, the forensics used to catch Ruxton, and his trial and execution. Out of respect for the families involved, we have chosen not to include those details here.

You can download a transcript of the diary below. Any publicly accessible references to the diary must be credited to Lancaster City Museums.