Yesterday's Everyday: Objects from the Cottage Museum

Can you imagine life without running water, electricity, central heating or even a toilet?

No? Then welcome to Lancaster’s own 18th century Cottage!

The Cottage Museum has been restored to show how a respectable yet modest household might have lived a little more than two centuries ago. The house still has most of its original features, and it’s filled with locally made furniture and objects from that era. Some of the everyday items in the cottage are still familiar to us today, while others may have fallen out of use entirely in our modern age.

Read on to find out how a few of these forgotten objects would have been used.

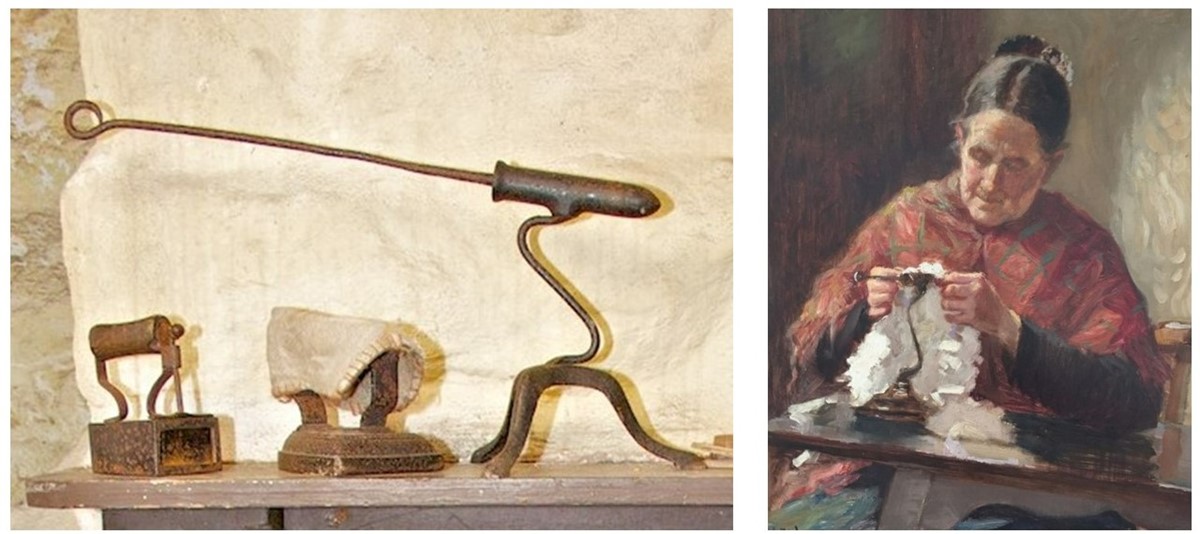

Goffering was the process of working fabric into frills that were evenly and finely gathered and crimped.

Many devices such as corrugated boards and rollers were used at various times to keep collars and ruffles nicely goffered and crimped. Goffering irons were introduced from Italy in the early 17th century, and the one in the washhouse at the cottage is a typical example of those in use by the middle of the 19th century. The iron’s specialised design would have been very useful for the ornate and delicate decorations that were fashionable in the Victorian era, particularly for small and finely gathered frills such as those on a high-quality baby’s bonnet.

The collars, cuffs, and ruffles of most garments were detachable. After being removed and washed separately, they’d require gathering and goffering before being sewn back into place.

The removable rod of the goffering iron was very like an ordinary fireplace poker. The tip would be thrust into a fire until it was red hot, then inserted into the rounded barrel of the iron, heating it from the inside. Fabric would then be gripped in both hands and pressed over the barrel to set it into a semicircular crimp. Producing even, firmly set frills in this way was a skilled job that required a good deal of practice.

Goffering irons continued in service until the end of the 19th century, when fashions began to move away from the copious ruffles of the Victorian era.

Until the dawn of the 20th century, most people lived without electric lighting or even gas lamps.

Candles were therefore a necessity of daily life, a reliable way of having light after dark. Candlelight was used for most activities including cooking and eating, reading and writing, sewing and housework. The fire in the hearth was often a major source of light, but candles would brighten up different areas and could be carried from room to room.

The candles in the Cottage Museum are made from tallow, a rendered form of beef or mutton fat. In the 1700s the average household would burn a single tallow candle for two hours each night. These candles produced a similar smell to bacon and other cooked meat, and this would of course attract vermin.

Consequently the candle box became popular. These were designed to protect the candles from being eaten by rats and mice. The box would usually be mounted high on a wall and kept firmly closed. The one on the parlour wall in the Cottage Museum is made of metal, so nothing could gnaw through it.

Butter is most often produced from cows milk, but the milk from sheep, goats or any other mammal can also be used. Butter is made by churning the milk or cream to separate fat globules from buttermilk. Before the advent of factories, butter was made by hand on a small scale. On a smallholding with only a few cows, cream would have been collected from several milkings and would have been a few days old - and somewhat fermented - by the time it was made into butter.

After it was churned, butter pats were used to shape the butter into a brick. The butter maker would use a pair of butter pats with one held in each hand to work the butter into shape. The wooden butter pats were washed in salted water to help prevent the butter from sticking to them. The inside face is serrated to grip the butter and squeeze out any surplus watery buttermilk. They could scoop, stir, cut, slap and lift. The butter pats would also make a pattern on the finished butter.

Butter pats continued to be used well into the 20th century and were also known as butter paddles, beaters, spades or Scotch hands. You’ll find our set in the larder of the cottage. The worktop here was originally a solid slab of stone which helped to keep food such as butter cool. Sadly, it was removed in the 1960s to allow the installation of a modern kitchen - almost the only significant change made to the cottage in the 20th century.

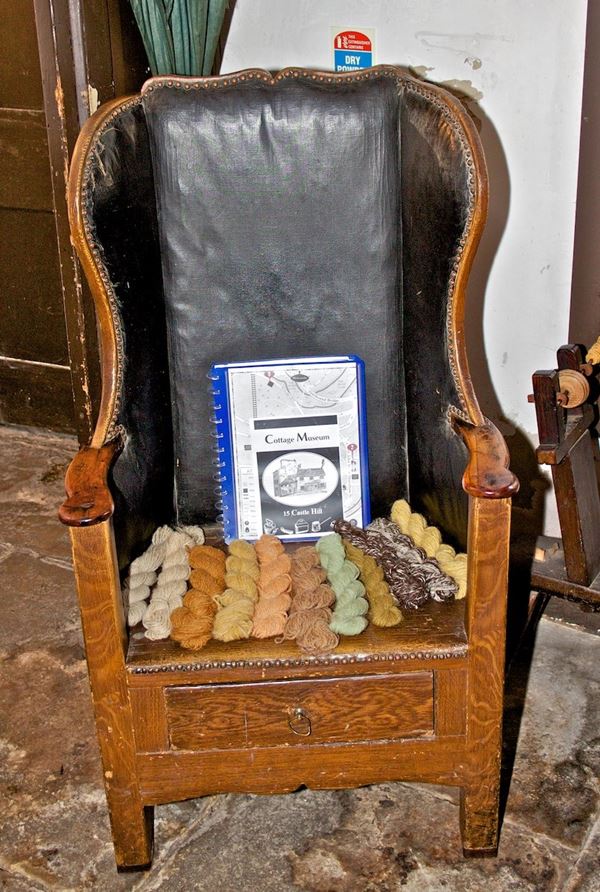

The wingbacked wooden armchair in the parlour of the cottage may look ordinary at first glance, but in fact it’s a specialised piece of furniture originally designed for use on a sheep farm. At lambing time the chair would be taken outdoors for a shepherd to rest in while keeping watch and awaiting new arrivals. Lambing usually occurs in early spring, and the weather can be harsh. Traditional farmers needed to be on hand night and day in case of problems, especially with first-time mums. Even when a birth goes smoothly, the ewe will occasionally be unable to look after all her lambs. The lambing chair features a drawer beneath its seat where a rejected lamb could be placed on a bed of hay to keep it warm. Meanwhile the high back and wings helped to protect the shepherd from the elements. The chair is designed for comfort during a long vigil, though without much upholstery, which would easily be ruined by rain.

Lambing chairs are a great example of regional vernacular furniture. They were widespread in Lancashire and the Yorkshire Dales from around 1750 to 1850. Outside lambing season they were a common sight in farmhouse kitchens and would hold pride of place at the fireside. The high winged back protected the occupant from draughts indoors as well as out, and the drawer provided useful storage. The style of individual chairs varies, as the market wasn’t large enough for mass production - they would have been made to order by local cabinet makers or carpenters.

So what’s it doing in the cottage? The centre of Lancaster today may seem a long way from a farm kitchen, but a couple of centuries ago, this was a market town with close connections to the countryside. It would have been common for a modest town house like the cottage to contain some second-hand furniture that started life on a nearby farm. Look around and you’ll find that this chair is part of a motley collection. Some pieces of furniture (such as the simple but sturdy rope and timber bed upstairs) would have been bought new, while others (like the finely turned cot in the second bedroom) may have been handed down from wealthier friends or relatives.

Open fires were the only means of cooking in the cottage. There's a metal crane above the fireplace in the parlour for hanging pots and pans, but there is no built-in oven or range. That's where this device comes in. Known as a Dutch oven or reflecting oven, it's essentially a rounded metal box that's open at the back. Hanging from the frame at the top is a brass clockwork jack, from which a joint of meat can be suspended inside the oven. Placed in front of a fire, the clockwork turns the meat slowly while the metal sides help to reflect the fire's heat towards it. The oven is light enough to move around easily so it can be stored elsewhere when it's not in use.

Dutch ovens like this became common in the 1700s, although a variety of similar devices were in use much earlier.